I dragged a (quite willing) friend along with me on a day excursion to Fliess (around here written Fließ), a village up on a mountainside overlooking the Upper Inn Valley. The main reason was to visit the Archaeological Museum, home of an impressive number of Roman and pre-Roman objects found in the area. While we enjoyed the Museum immensely, the journey there offered a surprising number of delights.

We had planned to take a Postbus from Landeck, but were given some misleading information (we had not realized that we were to take the bus that passes in the valley below, and walk up from there) and so we decided to walk rather than wait, and to take the trail over Landeck Castle. Without planning to, we found ourselves on the old road bed of the Via Claudia Augusta, the Roman road which ran along a portion of the Inn River on its way to Augsburg. The “Claudia” part is for Emperor Claudius, who had it built. His father Drusus, adopted son of Caesar Augustus, was responsible for the Roman march over the Alps and into northern lands.

Heumanderl, or hay racks, in a field. My friend told me a legend about our local hero Andreas Hofer using these “hay men” to make Napoleon’s troops think he had a larger army than he had.

Dramatic Squirrel has an Alpine cousin — and he’s black.

Another reason to come to Fliess was to see the Schalenstein at the Philomena Chapel, just outside the village.

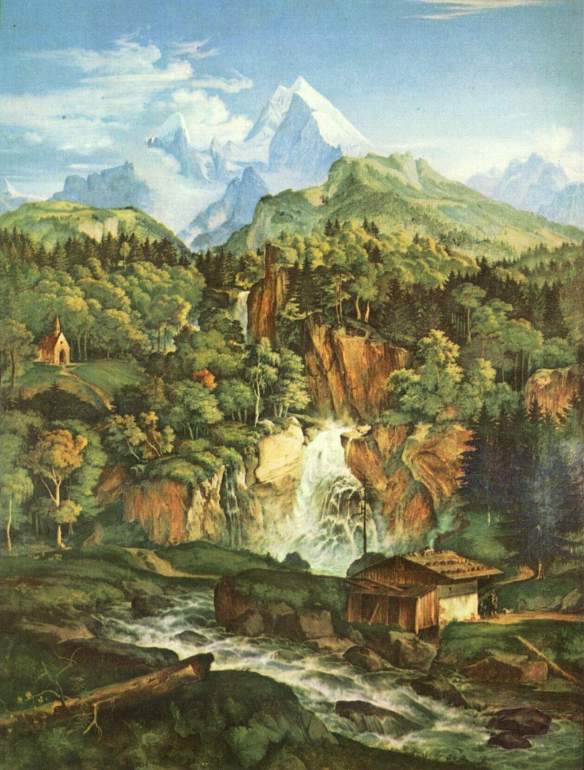

The chapel was built in or around 1749. Inside, directly behind the altar hangs a painting (with reliquary) of the virgin martyr Philomena, “lying in her grave in the catacomb”, according to the information plaque on site, although she appears to be quite comfortably settled in a chaise longue. Philomena is one of those quasi-saints who were not only never canonized, but who was purged from the liturgical calendars in 1961. Her golden pendant is a reliquary for something so tiny that we could not make out what it was — possibly a bone sliver?

Ah, and here, finally, behind the church, the Neolithic Schalenstein with 70-90 markings, one of the most prominent of its kind.

A post on the Archaeological Museum to follow shortly.