Edited English-language intro: as the course for which I wrote this post is being offered once again, I have begun to remove references to it out of concern that someone will find this post via keywords and then just cut and paste. I would like for that not to happen.

2011 schrieb ich über einen Besuch bei den archäologischen Grabungen an der Hinterseite des Bergisel. Ich habe diesen Beitrag nun hervorgeholt, um ihn bei meinem Archäologiekurs zu verwenden – um einen Fall über die Bewahrung von Funden zu beschreiben und zu zeigen, ob die Anstrengungen von Erfolg gekrönt waren oder nicht. Die Übung, diesen Beitrag nun in einem anderen Lichte zu schreiben, brachte mich dazu meinen bisherigen Ansichten zum Fundort und den Arbeitsschritten zu überdenken. Der Kulthügel am Bergisel ist eigentlich sowohl eine Rettungsgrabung alsauch ein Vermächtnis. Im Geiste der Teilhabe veröffentliche ich daher diese neue und verbesserte Version des damaligen Beitrags.

(Photo from kone.com )

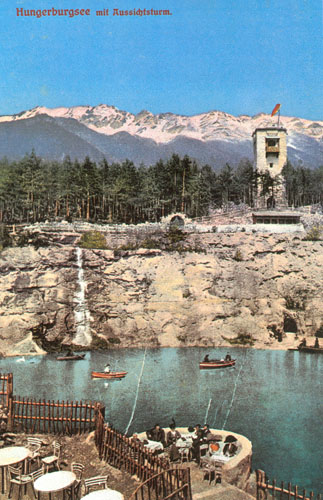

Bergisel is known today as the site of one of the “Four Hills” ski jumps (and a very nice one at that). You may have seen the ski jumping competitions held here on television. The area is also used for concerts, New Year’s Eve fireworks displays, World Cup soccer match broadcasts on large screens, the annual “Air&Style” Freestyle Snowboard Festival, and is the location of the new Tirol Panorama Museum. There is also a pretty trail along the Sill Gorge, on the back side of the hill. It has, therefor, somewhat heavy human traffic at certain times during the year. Bergisel was also known to be a significant archaeological site since the 1840s, when a small military museum was built on a lower slope —the partial collection of a large treasure find is housed in the Tirol State Museum Ferdinandeum, the other part having been “carried off by the wagonful and sold by weight to bellmakers”.

Der Bergisel ist heutzutage bekannt als eine (besonders schöne) Station der Vierschanzentournee. Vielen wird der Bergisel von Fernsehübertragungen der Schisprungveranstaltungen bekannt sein. Das Gelände wird auch für Konzerte, Neujahrsfeuerwerke, Fußballübertragungen auf Großleinwand und dem jährlichen Air&Style Snowboard Festival genutzt. Zudem ist es der Standort des neuen Tirol Panoramas. Es gibt auch einen reizenden Steig durch die Sillschlucht, an der Rückseite des Bergisel. Der Platz ist somit im Jahreslauf zeitweise von Besuchern stark frequentiert.

Der Bergisel ist als herausragendes archäologisches Fundgebiet seit den 1840ér Jahren bekannt, da man damals ein kleines Militärmuseum am unteren Hangteil errichtete. Ein Teil der damaligen funde sind im Tiroler Landesmuseum ausgestellt, während eine anderer Teile als „Wagenladung weggeschafft und nach Gewicht an Glockengießer verkauft wurde“.

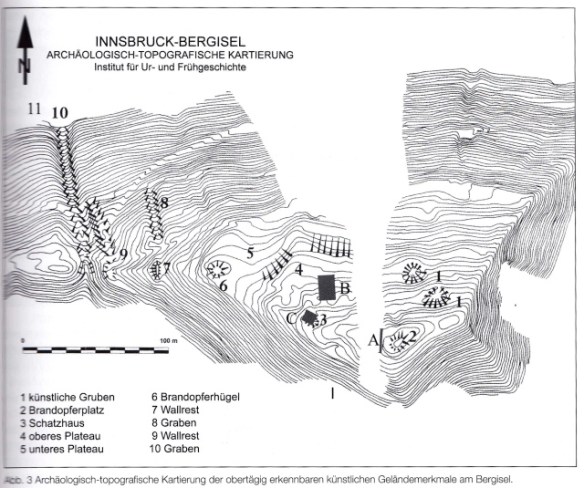

Top image is a screenshot from Bing Maps. Bottom image is from “Ur- and Frühgeschichte von Innsbruck” (“Prehistoric and Protohistoric Archaeology of Innsbruck”) catalog accompanying the 2007 exhibit at the Tiroler Landesmuseum Ferdinandeum, Innsbruck. In German.

When the old jump was built for the 1964 Winter Olympic Games, a large swath of earth had been removed, and a great deal of archaeological evidence unfortunately went with it. This jump was demolished in 2001 to make room for a better, modern one planned by the well-known architect Zaha Hadid, and in between local archaeologists from the University of Innsbruck were able to come in for a limited time and do excavations.

These excavations have uncovered a site for burnt offerings near the highest point of the hill, just a few meters east of the ski jump tower. Animal bones were found which had been burnt at a temperature of over 600°C. These artifacts have been dates to ranging from 650 BCE to 15 BCE, when the Romans arrived, and would have been taken to the Ferdinandeum.

Als die alte Schisprungschanze für die olympischen Spiele 1964 gebaute wurde, wurde eine mächtige Erdschicht und zugleich eine große Menge archäologischer Beweisstücke entfernt. Diese Schanze wurde 2001 abgetragen und durch einen besserer und modernere von der bekannte Architektin Zaha Hadid geplante ersetzt. Ein begrenzte Zeit konnten Archäologen der UNI Innsbruck Ausgrabungen durchführen.

Bei diesen Ausgrabungen wurden verbrannte Opfergaben nahe der Spitze des Berges, wenige Meter östliche des Schanzenturms entdeckt. Bei 600°C verbrannte Tierknochen wurden gefunden. Diese Fundstücke wurden Zeitraum zwischen 600 und 15 v.Chr., vor Ankunft der Römer, datiert und ins Ferdinandeum gebracht.

The features, that is, the larger artifacts, were then back-filled with earth and left alone. There was absolutely NO information found (in 2012) at the site itself, which is on the outside of the fenced-in ski jump area, so one can’t just take the incline to visit it. There are barely trails — animal paths really — up the very steep grades on the back end of the hill. There are no signs forbidding access but it is difficult to get up there. ( I only made it up —and down — by grabbing onto tree roots and watching very carefully where I stepped. Dead leaves, pine needles and pine cones added a certain hair-raising slipperiness to the adventure. )

Die Bodenmerkmale, also die größeren Fundstücke, wurden dann wieder mit Erde verfüllt und sich selbst überlassen. Es wurde absolut kein Hinweis auf den Fundort außerhalb des umzäunten Geländes der Sprungschanze hinterlassen, sodass man nicht die Möglichkeit hat, den Ort mit der Standseilbahn zu besuchen. Es gibt kaum Pfade den steilen abhängen der Hinterseite des Berges hinauf; die vorhandenen sind tatsächlich Trittspuren von Tieren. Es gibt keine Schilder, die den Zutritt verwehren, aber es ist auch nicht leicht dorthin zu kommen. (Ich selbst kam nur rauf –und runter – in dem ich mich an Baumwurzeln hochhantelte und genau achtete wohin ich trat. Alte Blätter, Nadeln und Tschurtschen (Föhrenzapfen) erweitern das Abenteuer um haarsträubenden Rutschigkeit)

Photograph by the author.

The altar mound as seen today, on the highest point of the hill. The fence around the sport area runs right through the mound, which seems a little unfortunate. I do not know the impact of the fence on the re-buried site but hope that it is minimal.

My take on this site is that despite the great loss of artifacts from earlier landscaping and construction, archaeologists have done their best to secure it and keep it removed from human disturbance as best they can. They had been extremely pressed for time before construction on the new tower began. Today nearly all visitors experience the Bergisel at the lower end, where the Panorama Museum is located, or take the incline ride to the cafe inside the ski jump tower (or walk up on the concrete steps) and have no interest in wandering over to the unidentified excavation site. This makes the conservation efforts a success. A prognosis is more difficult, as I do not know what plans the property owners have for the area. As long as it remains as it is, the site is secure.[submitted summer 2013]

Der Kulthügel, wie man ihn heute sieht, liegt am höchsten Punkt des Berges. Der Zaun der Sportarena läuft direkt durch den Hügel, was etwas unglücklich erscheint. Ich weiß nicht, welche Auswirkungen das Zaunfundament auf die darunter vergrabene Fundstätte hat, hoffe aber, dass diese gering bleiben. Meinen Meinung über diesen Fundort ist, dass die Archäologen trotz der großen Verluste an Fundstücken durch frühere Geländeveränderungen und Bauarbeiten ihr Bestes getan haben, um das verbleibenden zu sicheren und vor menschlichem Zugriff zu bewahren. Sie handelten während des Baues der Sprungschanze unter großem Zeitdruck .

Heute erleben die Besucher den Bergisel vor allem am unteren Ende, wo das Panorama-Museum steht, oder fahren mit der Standseilbahn zum Cafe im Schanzenturm (oder gehen über die Stufen der Tribünen), haben jedoch kein Interesse über die unbekannte Ausgrabungsstätte zu wandern. Die sicherungsmaßnahmen der Archäologen sind somit erfolgreich. Eine Prognose ist hingegen schwierig, da ich die Pläne der Grundstückseigentümer nicht kenne. Solange es so bleibt ist der Fundort sicher.

Additional source link: http://www.uibk.ac.at/urgeschichte/projekte_forschung/archiv/archivprojekte-tomedi/03_02.html (in German)