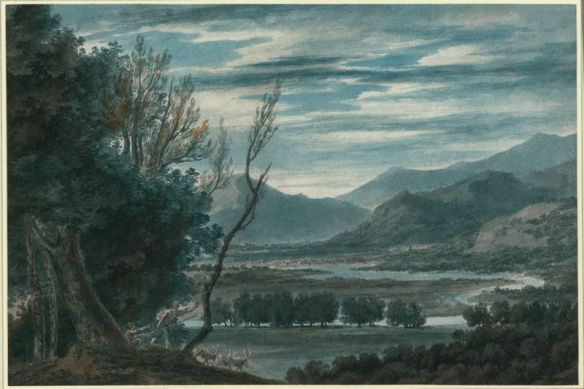

I had already been toying with the idea of a series of alpine paintings accompanied by photos of the mountains which inspired them, when Paschberg sent me the link to this watercolor by the 18th century British artist John Robert Cozens, with the somewhat clunky but informative title The Valley of the Eisak Near Brixen in the Tyrol, 1783/84. It currently belongs to the Art Institute of Chicago.

Looking around online for more information, I found a “2.0” version; In the Tyrol, the Valley of the Eisack, near Brixen, 1791 The painting, like the name, is similar but not identical — the view looks to be from further down on the floodplain, closer to the winding river. This version belongs to the National Gallery of Canada.

Near Brixen, June 7 appears to be the original sketch for both paintings. The Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection owns it…

…as well as this sketch with the same name. Since they are both dated June 7, one can assume the two scenes are not far away from each other. Perhaps all Cozens did was turn around, and sketch the view in the opposite direction.

There are tentative plans for a trip into that area next month. I can’t spend days hunting down this particular place but I’m going to keep my eyes open for it. The river may have changed since Cozen’s trip (dredged, straightened) but the mountains will still be there.

*Brixen is a town in the German-speaking, northernmost region of Italy. The Italian name, which may be all you find in an American atlas, is Bressanone.