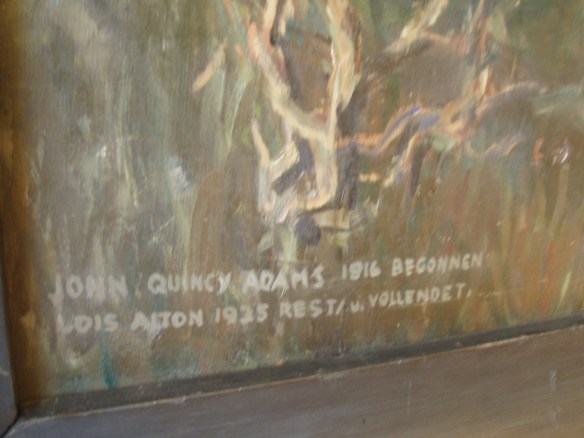

The site of the long log house today.

The site of the long log house today.

When Theophilus Gates, the founder of the Battle-Axe religious movement, passed away in 1846, the “indomitable” Hannah Williamson succeeded him as leader among the saints. She was already well-known in “Free Love Valley”, preaching and prophecying in the fields and roads.

She also became attached to the Stubblebine family. One mate, however, could not suffice for this remarkable woman. In the long log house near the Cold Springs, lived young Dave, Dan and Hannah. Dave was a carpenter, Dan a smith. The brothers farmed a little, but their specialty was small hand coffee mills. Dave did the woodwork, Dan the iron, and when they had a supply they took them to Philadelphia. The carpenter shop was in the log house, the smithy back in the woods, and there was a springhouse over which Hannah had a room for herself.

The state had already seized a thousand dollars in cash, cattle and farm goods for the support of Dave’s discarded wife. When his brother-in-law had endeavored to inform Dave of the hearing at Court upon this question of who was to provide for the upkeep of Catherine Stubblebine, he had refused to receive the paper, or to hear it read, observing that it might as well have been left in West Chester, and that no honest man would have anything to do with it. Catherine continues to live with her brother in the valley, and was an important witness at the trials of 1843, where her husband was dealt a sentence of eighteen months imprisonment.*

…

Hannah, as the world was learning, thought and acted in superlatives, measured life in the grand proportions which her torrential emotions demanded. When she found herself with child, it was a new messiah that was to be born, and when the baby died, it was laid away to await a mighty resurrection. Twice “Christ” was born in the log house, and buried, once under a great Chestnut tree nearby, once in a field by the road.

Valley children used to pick through for the log house’s rubbish heap for discarded round pieces of wood, cut from the tops of the coffee mills, to make wheels for their wagons.

But it was always with a thrill of terror that they passed the small hollows in the ground that marked the graves. At night, with the tangled shadows and the ghostly rustling of the woods about one, it was a difficult matter to get past at all. Even older people had a solemn stare for the places “where they buried Christ.” The neighbors feared both the place and its people. Israel Miller said he would not go to the log house for the best horse you could give him.

Text from “Theophilus The Battle-Axe”, Charles Sellers, 1930. Patterson & White, Philadelphia.

* Along with several others, for disregard of marriage law.