The Lanser Kopf (“Lans Peak”)

is a rocky outcropping atop a wooded hill called the Paschberg, situated between Innsbruck, Austria, and the village of Lans. It sits just under 300 meters above the city, and a hike to the top can be done in about an hour. It is one of the few lower hilltops which has not, to my knowledge, been previously excavated.

Übernommen aus einem kürzlich verfassten Beitrag für einen Archäologie Online Kurs an dem ich teilnehme.

Der Lanser Kopf liegt auf dem Paschberg, zwischen Innsbruck und der Dorfgemeinde Lans, knapp 300 Meter über der Stadt, wovon man in ca. eine Stunde eine gemütliche Wanderung machen kann. Er ist eine der wenigen Mittelgebirgsebenen in der Gegend auf der man, so weit ich weiß, keine archäologischen Ausgrabungen durchgeführt wurden.

Innsbruck, Paschberg/Lanser Kopf, Patscherkofel (2246 m)

Innsbruck, Paschberg/Lanser Kopf, Patscherkofel (2246 m)

One of the most interesting things about the Lanser Kopf is that there are multiple of evidences of use over time. Schalensteine (rocks with cup markings) can be found on the lower slopes. Unfortunately it is impossible to date them. It is suspected that there may also be markings in the rocks at the peak, but these are partially covered with trees, earth and concrete. The concrete, poured in the middle of the last century, holds park benches and a marble table, and also makes up two WW2 Two flak circles. The circles were abandoned at the end of the war, and now have trees growing inside them.

Eine Besonderheit des Lanser Kopfs liegt in seine vielseitige Nutzung im Laufe der Zeit. Auf dem niedrigeren Hang findet man Schalensteine, die leider nicht datierbar sind. Man vermutet, dass man oben an der Spitze auch Schälchen finden könnte, wenn die Steine nicht mit Erde, Bäumen und Beton verdeckt worden wären. Der Beton wurde in der Mitte des vorigen Jahrhunderts am Kopf gebracht, um Parkbänke und eine runden Marmortafel zu befestigen, und wurde auch im zweiten Welzkrieg für die Herstellung von zwei Plattformen für Fliegerabwehrkanonen (FLAK-Kreise) verwendet. Bäume wachsen jetzt in den leer stehenden Kreisen.

Two WW2- era flak circles at the Lanser Kopf.

Two WW2- era flak circles at the Lanser Kopf.

The earliest humans artifacts found in this region date back to about 30,000 BCE . Evidence of Bronze Age and Iron Age settlements have been discovered on other nearby hilltops, including stone residential terraces (Hohe Birga, Himmelreich), and sacrificial burning sites (Goldbichl, Bergisel.)

Die älteste prähistorische Artefakte aus dieser Gegend datieren auf 30,000 v. Chr. Neolithische Siedlungen hat man an naheliegenden Hügeln entdeckt, Steinterrassensiedlungen (Hohe Birga, Himmelrich) und auf Brandopferplätze (Goldbichl, Bergisel).

As far as I know, the Lanser Kopf was not used for anything in the Modern Era — with the exception of the wartime use — other than as a place to rest while hiking. There is no obvious evidence of it having been used for farming or settlement. However, it’s use in the last century as a strategic point for sighting enemy planes and firing missiles at them certainly would have roughed up the area somewhat, since it can been assumed that military jeeps or trucks would have been driven at least to the plateau just below the flak circles, and the construction of the circles themselves would have affected any older formation processes.

So weit ich weiß hatte der Lanser Kopf in der jüngeren Geschichte, außer während der Kriegszeit, nie eine besondere Funktion. Es gibt dort keine offensichtlichen Anzeichen von Siedlung oder Landwirtschaft. Er diente als Rastplatz für Wanderer. In den Kriegsjahren war die Gegend mutmaßlich von LKWs und Jeeps überrollt, und die Herstellung der FLAK -Kreise hätte ältere Spuren zerstört.

This, however, brings forward another question — which kinds of artifacts does one wish to find? There may well be modern(ish) war artifacts in the vicinity, from either the Second World War or from the battles against Napoleon’s troops in 1809. There may be man-made objects just below the surfaces.

But could be there also be older signs of human settlement below the flak circles? One would unfortunately have to destroy them in order to see what lies below. And while the concrete flak circles may not be of much interest to people today, I find it important that they remain, as an historical testament to Innsbruck’s war involvement in the 1940s. I find that it would not be worth it to remove them in the search for earlier artifacts. The earth-covered level area just below them, however, would be a worthy site for excavation, indeed if such work hasn’t been done already.

Das alles wirft eine Frage auf: Welche Artefakte erwartet man zu finden? Es gibt wahrscheinlich schon genug Kriegsartefakte aus dem zweiten Weltkrieg oder, weiter zurück, vom Tiroler Volksaufstand in 1809. Könnten prähistorische Funde direkt unter den FLAK-Fundamenten liegen? Man müsste diese aber zerstören, wenn man dort richtig graben will. Obwohl sie heutzutage wenige Leute interessieren, würde ich lieber sehen, dass sie intakt bleiben, als historische Zeitzeugnisse der Kriegsjahre Innsbrucks. Hingegen läge auf der kleinen Ebene etwas unterhalb der kreisförmigen Fundamente eine angemessen Stelle für eine Ausgrabung, wenn nicht solche schon durchgeführt wurden.

From evidence gathered by archaeologists, pre-Roman-era settlers in Tirol greatly preferred the high plateaus and hilltops between the Inn (swampy floodplain) and the mountains (rocky, barren). This middle ground was probably ideal for hunting as well as providing safety. Since the arrival of the Christian missionaries in the Middle Ages, many of those hilltops have been adorned with chapels. It has been speculated that these chapels might be sitting atop the remains of pre-christian structures, and often successful excavation work has been done in their immediate vicinity. If such an excavation were done on the Lanser Kopf, one might look for pre-historic arrowheads, ceramics, stone objects, weapon depots and offerings (of which there are many in the Alps) or sacrificial burning sites, all of which have been found elsewhere in the region.

Aus archäologischen Befunden in der Region wissen wir, dass viele vorrömische Siedlungen in den Mittelgebirgen eingerichtet wurden, wo die Ureinwohner mehr Sicherheit und bessere Lebensqualität vorfanden. Seit der Ankunft christlicher Missionare im Frühmittelalter, sind viele dieser einigermaßen höheren Stelle mit Kapellen geschmückt. Man könnte vermuten, dass manche dieser Kapellen möglicherweise auf Resten von früheren, vorchristlichen Bauwerke stehen, und tatsächlich hat man neben solchen Kapellen erfolgreiche Ausgrabungen durchgeführt. Wenn man so eine Ausgrabung auf dem Lanser Kopf unternähme, fände man möglicherweise Artefakten wie Pfeilspitze, Keramik, Steinfiguren, Waffendepots oder Brandopferstätte, welche anderswo in der Region, auf höheren Stellen, bereits gefunden wurden.

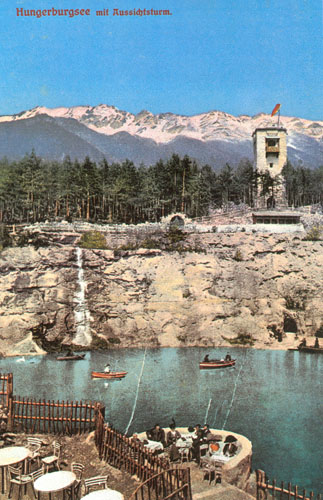

In 1912 a hotel was built up on the Hungerburg (a high plateau above Innsbruck), at the site of an old quarry. The quarry was flooded with water from the mountain spring, an observation tower was erected above the lake, and the whole thing was planned to be used as a little mountain resort, called the Seehof.

In 1912 a hotel was built up on the Hungerburg (a high plateau above Innsbruck), at the site of an old quarry. The quarry was flooded with water from the mountain spring, an observation tower was erected above the lake, and the whole thing was planned to be used as a little mountain resort, called the Seehof.

Then and now: from almost the same vantage point. Below: the observation tower is still standing, but of course the area is private property and fenced off from random visitors. One can walk right up to the back of the tower, however.

Then and now: from almost the same vantage point. Below: the observation tower is still standing, but of course the area is private property and fenced off from random visitors. One can walk right up to the back of the tower, however. Since 1951 the property has belonged to the Arbeiterkammer (Austrian Chamber of Labour) and after a few renovations the building is now a thoroughly modern training center with conference rooms and the like. But sadly it seems the lake is gone forever.

Since 1951 the property has belonged to the Arbeiterkammer (Austrian Chamber of Labour) and after a few renovations the building is now a thoroughly modern training center with conference rooms and the like. But sadly it seems the lake is gone forever.