OK, I did a little more searching on the internet, and found that there is more to be found under “Grabhügel” than there is under “Hügelgräber” (which is the word used on the Schondorf municipal website.) A lot more. Between the Ammersee and the Lech river alone there are 167 mounds. In Grafrath, just a ways up the road, there are 250 mounds, old stone-age fortress remains, and a sacrificial stone complete with cup markings. In other words, the place is teeming with pre-historic geological archeological finds. So little time!

Author Archives: kcosumano

Pagans in Bavaria: Celtic Grave Mounds

On my hiking map of the Ammersee region, I found two red stars placed on a wooded area north of Schondorf. The map’s key uses this symbol for grave mounds or ringwalls, a number of which are to be found in Bavaria. Surprised to find some just down the road, we set off to look for them. Going mainly by instinct, we turned off the road at the big strawberry between the Aldi and Schondorf and parked there, then headed into the woods on foot.

This was not the ideal entrance point, but we couldn’t find a better one. Trying to walk toward the place indicated by the stars, we veered off the path pretty early. On the other side of some swampy grassland surrounded by forest, I could make out something that looked higher than the rest of the forest floor.

This was not the ideal entrance point, but we couldn’t find a better one. Trying to walk toward the place indicated by the stars, we veered off the path pretty early. On the other side of some swampy grassland surrounded by forest, I could make out something that looked higher than the rest of the forest floor.

I think this is a mound. The Beau was not entirely convinced. No signs, no path, just strange little hills covered with trees and moss, and a hell of a lot of biting insects (I was wearing shorts — “typisch amerikanisch”, said the Beau — a mistake I won’t make again.)

I think this is a mound. The Beau was not entirely convinced. No signs, no path, just strange little hills covered with trees and moss, and a hell of a lot of biting insects (I was wearing shorts — “typisch amerikanisch”, said the Beau — a mistake I won’t make again.)

Here appear to be three. It’s not easy to tell in the photos, but they really were different from the surrounding landscape. (Of course, it’s impossible to tell just by looking — hills like this could have nearly anything underneath them, from old war debris to landfill. ) Local websites mention that there are fourteen such Celtic grave mounds in the area, but nothing more about them. We’ll keep looking.

Here appear to be three. It’s not easy to tell in the photos, but they really were different from the surrounding landscape. (Of course, it’s impossible to tell just by looking — hills like this could have nearly anything underneath them, from old war debris to landfill. ) Local websites mention that there are fourteen such Celtic grave mounds in the area, but nothing more about them. We’ll keep looking.

R.I.P. Patrick Leigh Fermor

I first came across the name Patrick Leigh Fermor in a biography about Bruce Chatwin; he and Robert Byron were his predecessors and influences in travel literature, and they were so neatly described that I immediately ordered old, out-of-print copies of Fermor’s “A Time Of Gifts” and Byron’s “The Road To Oxiana”. These books marked the beginning of a long and happy interest in the writings of people who have grabbed a rucksack and gone off to find adventures in a changing world.

It took me years, however, to get around to ordering the second installment in the planned trilogy, and the third book has yet to come out (although I was happy to read in Fermor’s obituary that a final draft may indeed have been completed, and may actually get published, in my lifetime I would hope…) I can’t be too saddened to hear of his death, at age 96. He lived a long, full and happy life, and cheered many, many people along the way with his delightful stories.

Das Tirol Panorama

There was finally time for a visit to the Panorama Museum, home of Innsbruck’s historic Riesenrundgemälde, previously displayed in the Rotunde in town. The interior is all modern glass and concrete, but they’ve done nice work with the presentation of the old-timey panorama painting, which still has its charms. One particularly strong impression is one of the very first — you have to descend an escalator to a lower level and then walk up a set of stairs to get “into” the panorama, and from the bottom of the stairs you see the Northern Range, and for a second you really aren’t sure if it’s not the real thing you’re looking at. Later in the connected Kaiserjägermuseum you find yourself looking up another set of stairs, at the top of which is a large picture window which does look out on the real Northern Range, and then you realize what the architect was up to.

There was finally time for a visit to the Panorama Museum, home of Innsbruck’s historic Riesenrundgemälde, previously displayed in the Rotunde in town. The interior is all modern glass and concrete, but they’ve done nice work with the presentation of the old-timey panorama painting, which still has its charms. One particularly strong impression is one of the very first — you have to descend an escalator to a lower level and then walk up a set of stairs to get “into” the panorama, and from the bottom of the stairs you see the Northern Range, and for a second you really aren’t sure if it’s not the real thing you’re looking at. Later in the connected Kaiserjägermuseum you find yourself looking up another set of stairs, at the top of which is a large picture window which does look out on the real Northern Range, and then you realize what the architect was up to.

Back downstairs, one proceeds into a large space with a lot of “tiroliana”, some of it hidden in secret compartments within wooden pillars, which looked popular with children. In the center of the room is a lot of political remnants (such as the horse’s head from a Mussolini statue from South Tirol, blown up by activists in 1961).

Back downstairs, one proceeds into a large space with a lot of “tiroliana”, some of it hidden in secret compartments within wooden pillars, which looked popular with children. In the center of the room is a lot of political remnants (such as the horse’s head from a Mussolini statue from South Tirol, blown up by activists in 1961).

On the other side, a showcase of all manner of local “stuff”, past and almost-present. We didn’t quite get this part; it was as if the museum had to find a way to tie all these objects together and decided to display it almost randomly, with the archaeological finds right next to 20th-century mountain-climbing gear, insect display cases next to old crèches. Sometimes the explanatory signs were not easy to find. We decided that the snowboard must have been Andreas Hofer’s.

On the other side, a showcase of all manner of local “stuff”, past and almost-present. We didn’t quite get this part; it was as if the museum had to find a way to tie all these objects together and decided to display it almost randomly, with the archaeological finds right next to 20th-century mountain-climbing gear, insect display cases next to old crèches. Sometimes the explanatory signs were not easy to find. We decided that the snowboard must have been Andreas Hofer’s.

If you are visiting Innsbruck and want to see the Museum, I recommend taking the Nr. 1 streetcar to Bergisel (the last stop), then walking up the hill to the museum. There is also a restaurant with outdoor seating, and a gazebo from which to enjoy the view. Just across the park is the entrance to the ski jump arena, which also houses a cafe perched atop the jump, and more impressive views. This museum seems to be more for the locals than for visitors, but if you are interested in getting a sense of Tirolean history and culture without having to do much reading or traveling around, this could do it. The museum offers free headsets with audio tracks which explain what you are seeing. We did not take them, so I can’t tell you how they are.

A Surprise In The Kaiserjägermuseum

So, I finally made good on my promise and took my young friend to the still-new Tirol Panorama Museum on Bergisel. It’s connected to the Kaiserjäger Museum, which is dedicated to the Empire’s local militia regiments from the 19th century, so we wandered through that too, just looking at the paintings and the weapons with mild interest.

So, I finally made good on my promise and took my young friend to the still-new Tirol Panorama Museum on Bergisel. It’s connected to the Kaiserjäger Museum, which is dedicated to the Empire’s local militia regiments from the 19th century, so we wandered through that too, just looking at the paintings and the weapons with mild interest.

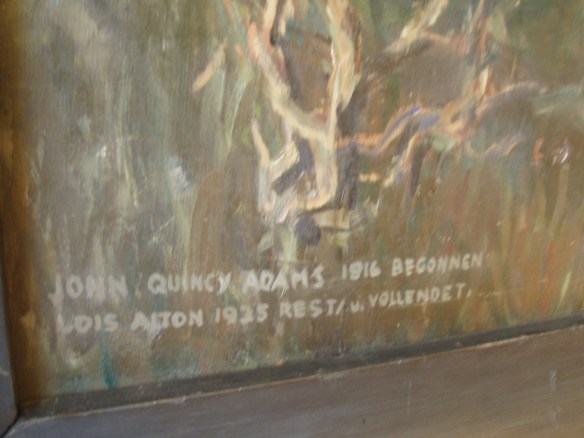

In one room my eyes rested on a large painting of soldiers greeting Kaiser Karl, the last Emperor of Austria. I found interesting the one soldier turning to look directly at the painter, and so my eyes dropped down to read the artist’s signature.

Say what? “John Quincy Adams, began in 1916. Lois Alton rest[ored?] and finished in 1935.”

Say what? “John Quincy Adams, began in 1916. Lois Alton rest[ored?] and finished in 1935.”

Not the U.S. President, but a descendant, 1874-1933. Interesting what Wikipedia (the German site) tells me — his father, Carl Adams, was a Heldentenor at the Vienna Court Opera for ten years, then brought his family back to America when John Quincy was four years old. At age twenty-six he enrolled in the Vienna Academy of Fine Arts, and went on to have a pretty successful career on both continents. He’s even got a grave of honor in Vienna’s central cemetery.

Here is another work, to show that it wasn’t all war paintings for him. Of Countess Michael Karolyi, from 1918. Very nice.

Here is another work, to show that it wasn’t all war paintings for him. Of Countess Michael Karolyi, from 1918. Very nice.

The restorer Lois, or Luis (short for Alois) Alton was a local artist of landscapes and portraits.

“Singers have become more interchangeable”

Singing legend, teacher and artistic director Brigitte Fassbaender was recently interviewed by Markus Thiel for the Munich newspaper Merkur. It’s honest and interesting, and there is a lot in it which explains how things are going for singers in European opera houses today, and so I present it here in translation (mine, and although it was done on the fly and therefor imperfect, I tried to capture the essence and tone of the interview as best I could.)

Brigitte Fassbaender is gearing up for some big changes. She will be leaving her post as Intendantin of the Tiroler Landestheater next season, after 13 years. Her successor will be Johannes Reitmeier. However, this legendary singer will remain active as head of the Richard Strauss Festival in Garmisch-Partenkirchen, which kicks off its summer season this weekend. She won’t be departing from the opera world just yet — this year Ms. Fassbaender celebrates 50 years of work on and for the stage.

Merkur: How difficult will it be for you to let go of your “child”, the Landestheater?

BF: I thought it would be harder. The house is functioning beautifully, everyone is highly motivated. But it has to happen. Theaters always need a breath of fresh air after a while. 13 years was enough — and I would also like to have a breathe of fresh air myself.

What did you have to learn when you first took on the position as Intendant?

It was an enormous learning process in every respect. I had to learn how to deal with so many people, with so many different personalities, temperaments, vanities, with workaholism, laziness, and also self-overestimation. But I found everyone to be highly motivated [to work with me]. One also feels a wave of affection from the side of the audience. As far as choosing works and the aesthetics of stage direction, I had hoped for more openness for other, less traditional ways. But that appears no longer to be possible anywhere. And so at some point I understood that I was working for the audience, not for the Feuilleton [the arts section of a newspaper, where theater reviews appear].

Is the intendant with artistic background an endangered species?

Yes. Those who really understand something about singing are dying out. Most of them only see a singer “as is” and cannot hear the potential for further development [in a voice].

Why is that?

I don’t know. Maybe because singers have become more interchangeable. There had always been only a handful of one-of-a-kind voices out there. But now it seems to me that everyone resembles everyone else. They all look alike as well! I look at a photo, I think it’s Elina Garanca, and it turns out to be a model for cosmetics… Singers are trying to copy this high-gloss effect. I find that unfortunate. The only one in my opinion who has been able to endure this unscathed is Anna Netrebko. She is a top artist with a healthy portion of humor about her. We had this danger in our day too. But back then one said “no” more often. I find it better to keep oneself scarce.

Are you happy to have made your career during the time in which you did?

It was very different then, there was much less stress and competition. There wasn’t this extreme casting by type. Female singers with more robust figures still had a chance. And we had more opportunities to sing for recordings and to take more risks in our work. For that I am happy.

How do you feel, looking back [on your career]?

Gratitude, but also amazement. For all the wonderful, strenuous, many-sided, nerve-wracking things that I was allowed to experience. Two-thirds of my professional life flew by me like a dream. I haven’t had time yet to get nostalgic. I consider myself a modern individual. When one doesn’t try to fit the current trend, one stays timeless — I have always tried to live by this motto.

Can you listen to your own voice?

In the meantime, yes, earlier, I was afraid of the possible disappointment. But now I think, “I like that voice. I would hire that young mezzo.” (laughing)

Were there ever times when you wished you hadn’t been a singer?

I have always suffered from terrible stage fright. Before every performance, before every recital, I would think, “No, I’d rather be raising chickens.” But surmounting those fears always led to great satisfaction. And one becomes more secure. I also suffered when I first had to make announcements before the curtain onstage in Innsbruck.

And have you gotten comfortable with your situation in Garmisch-Partenkirchen?

Very much! I am a self-confessed Straussian. Naturally I would like for it to be as top quality as possible — even if it is financially difficult to do so. I am dependent on my singers agreeing to be paid less that they normally would be, out of friendship. But then it is easier for them to cancel… it’s too bad that the state of Bavaria doesn’t think it necessary to give [the Strauss Festival] more support. We are constantly walking a tightrope, between top artistry and variety.

Richard Strauss has not only bright aspects to him. Has it been difficult, the work of rehabilitating the composer’s dark side?

BF: The Strauss family has given no obstacle whatsoever. They have been very open regarding his role in the National-Socialist years. Although I don’t know what they should do. His music was never overshadowed by his person. I don’t hear any anti-Semitism in it. Certainly there are works which are duty-bound to the attitude of that time — productions of them would naturally not be suitable. But what does a “Rosenkavalier” have to do with that? Strauss was simply business-minded and an opportunist. He thought himself and his family to be the center of the universe. It is a moral question — can or should one take artistic geniuses seriously for their politics? Hardly, I think.

>Es Lebe Der 1. Mai

>

Every May 1st at around noon, the Leftists get out their banners and march through the center of town. They’re peaceful enough, lots of families; the police presence assures no violence (I have never witnessed any myself, not even animosity from onlookers. Mostly a bland curiosity, maybe. It’s a different story in larger cities, but then it always is.)

This banner (which appears to be a new model, the old one had a yellow background)) still leaves me shaking my head. How can you march for socialism, democracy, peace, and against violence, racism and discrimination, alongside a banner with a portrait of Lenin, Stalin and Mao?

>Travel Blogging 4

>From “Theophilus The Battle-Axe: A History Of The Lives And Adventures Of Theophilus Ransom Gates And The Battle-Axes”, by Charles Coleman Sellers, 1930:

“A highly eccentric old lady of sixty-one years, Hanna Shingle [or Schenkel, or Shenkel] lived alone at the head of the Valley, just above the old church, in a little stone house surrounded by rocks and brambles and in a state of general disrepair. She had a few acres of ground which the neighbors tilled in return for a share of the produce. Her eccentricity [had] been traced to stern parents. It is said that she had been very handsome once, with curls down her back, and had ridden to church on horseback, to the admiration of all who saw her. Some of her wedding clothes had been made, and the time of the wedding near, when her parents found fault with her lover and intervened.

“Now we find Hannah Shingle a very peculiar old person, with a very small and slovenly farm, three cows, a sow and some pigs …. Small boys would come sneaking through the briars to steal her pears, scattering like startled deer as the old woman would rush from her door, an ancient and quite harmless musket in her hands, threatening death in her shrill voice. She had two weapons for her protection, the old gun and an axe. The gun was chiefly for small boys, the axe she kept under her bed, against more formidable intruders. There were rumors abroad that the old soul had laid away a hoard of gold, and an attempted robbery had increased her watchfulness. In October [1855] her sister visited and sought to persuade her to live with relatives, but Hannah had her gun and her axe and would not think of leaving.

She’s here somewhere, I used to know where the headstone was. Unfortunately many more are illegible now.

“A week later, John Miller, who was helping with the farm, found the door locked, and could get no answer to his knocking. He brought some neighbors and they forced an entrance. [Finding prepared food cooling in the otherwise empty kitchen,] …they stamped hastily up the narrow stair. In a little whitewashed bedroom above lay Hannah Shingle, her feet on the floor, her body and crushed head stretched out on the bed. There were marks of fingernails on her throat. The furniture was in disorder, the white walls splashed with blood, and there was a crimson pool on the floor, flowing out from under the bed. On a pillow, the murderer had left a bloody print of his bare foot, showing even the toenails. The robber had climbed a ladder to an upper window, probably in the early evening, and the old lady had left her cooking below to show him her prowess with the axe. It seemed obvious that the murderer was familiar with the ground, was someone in the Valley.”

(The culprit was never found. This is part of a somewhat longer history of the Valley which includes a naturalist, spouse-swapping religious sect, but that’s for another day.)

>Travel Blogging 3

>

>Travel Blogging 2

>

A little village near here, known for its historic gingerbread facades, fancy restaurant and rock falls, sprang up originally due to an iron mine and a quarry, both closed long ago. Behind the village are traces of the abandoned railroad which serviced the operations.

Most of the rail bed is now unmarked trail. The cinder bed remains visible, and some wooden ties here and there. The largest remains are the wooden bridges over the creek.

Above and below, two views of the same bridge.

A second bridge encountered closer to the road. When the mines were open (from 1845-1928), the hillside was barren. When they closed, the forest began to take over. The land now belongs to State Game Lands.