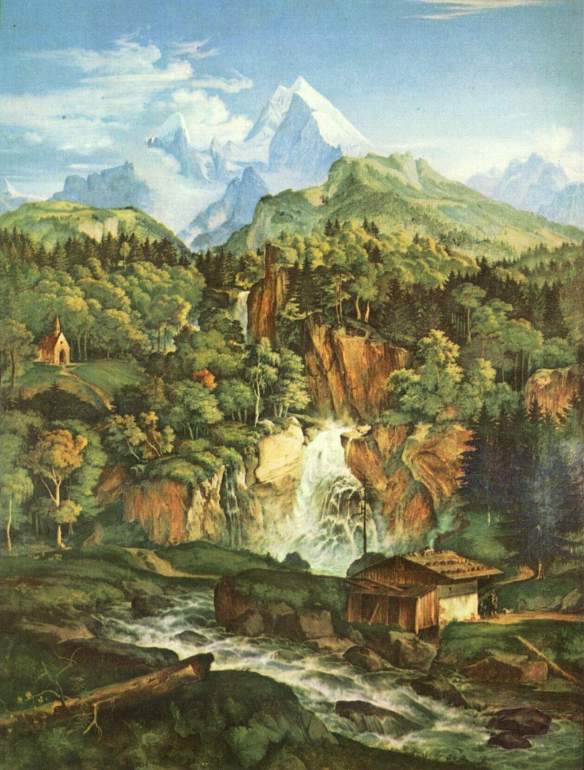

This is by Albert Bierstadt, the 19th-century painter who’s best known for his landscapes of the American West. It’s from 1868 and titled “Tyrolean Landscape“, but I am not so sure. There may very well be a duet of jagged mountain peaks in Tirol that look just like this…

…but it bears an uncanny resemblance to the Watzmann, which is in Berchtesgaden.(Image found here.

Yes, I can sense you shrugging your shoulders and rolling your eyes all the way from here — does it matter, you ask? Why yes, it does. Try calling a Tiroler German someday, see where that gets you. 🙂

And since Berchtesgaden belongs to a little dangling peninsula that’s surrounded by Austria, I looked on a map to see if it were possible that one could paint the Watzmann this large while actually standing in Tirol — nope, it’s Salzburg Land all around for kilometers. Was he (1) misinformed about his location, (2) is this indeed another mountain group, or (3) am I missing some important border realignment from the First World War?

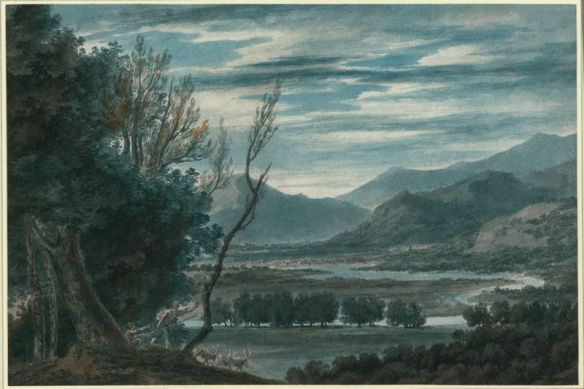

But as long as we’re discussing the Watzmann, here is one by Caspar David Friedrich, who had never actually seen the Watzmann with his own eyes and only knew the mountain from others’ works (come to think of it, we’ll call that (4) and it may be the best answer to the above question.)

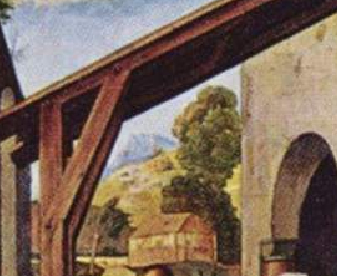

and one by Adrian Ludwig Richter, which I happen to like the most. It reminds me little of landscapes by the Tirolean artist Rudolf Lehnert.

Friedrich and Richter images found here.