Looking for other archaeology sites on the local map, one stumbles across other, less expected things. For example, a KZ (concentration camp) cemetery outside of the small lakeside town of Utting, where there had been a tannery which made use of forced laborers from Dachau — there were satellite camps all around, this was Camp 5 (Lager V).

Looking for other archaeology sites on the local map, one stumbles across other, less expected things. For example, a KZ (concentration camp) cemetery outside of the small lakeside town of Utting, where there had been a tannery which made use of forced laborers from Dachau — there were satellite camps all around, this was Camp 5 (Lager V).

We almost didn’t find it. In fact we had come to a dead end in a field and started to turn back, when a local came by on his bicycle. When he heard what we were looking for, he generously walked us there (we never would have found it on our own, once we saw where we were headed — through a patch of forest, someone’s back lawn and a wooded archery range — but we had come in from the wrong road, it seemed.

We almost didn’t find it. In fact we had come to a dead end in a field and started to turn back, when a local came by on his bicycle. When he heard what we were looking for, he generously walked us there (we never would have found it on our own, once we saw where we were headed — through a patch of forest, someone’s back lawn and a wooded archery range — but we had come in from the wrong road, it seemed.

About 500 male prisoners worked here from August 1944 until April 1945. This cemetery is for the 27 who died from the brutal treatment.

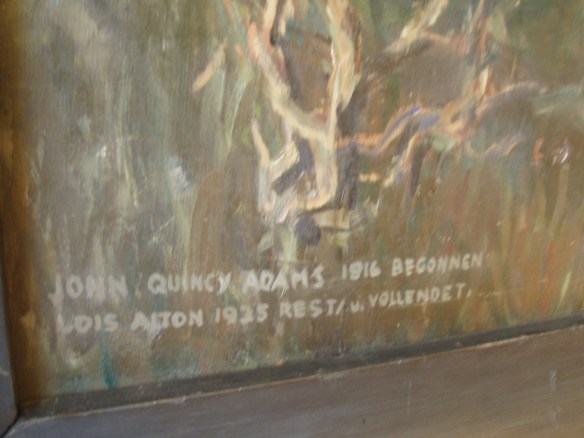

A large stone inside the cemetery wall commemorates the 27 victims, from “the rescued compatriots of Schaulen” (Šiauliai, in Northern Lithuania, was an important leatherworking town. Which explains why its sons were brought to the tannery).

A large stone inside the cemetery wall commemorates the 27 victims, from “the rescued compatriots of Schaulen” (Šiauliai, in Northern Lithuania, was an important leatherworking town. Which explains why its sons were brought to the tannery).

In my research I came across this poem by Yehuda Amichai, translated into English by Chana Bloch and Chana Kronfeld. The description could fit just about any of these little memorial graveyards, including this one.

“A Jewish Cemetery In Germany”

On a little hill amid fertile fields lies a small cemetery,

a Jewish cemetery behind a rusty gate, hidden by shrubs,

abandoned and forgotten. Neither the sound of prayer

nor the voice of lamentation is heard there

for the dead praise not the Lord.

Only the voices of our children ring out, seeking graves

and cheering

each time they find one–like mushrooms in the forest, like

wild strawberries.

Here’s another grave! There’s the name of my mother’s

mothers, and a name from the last century. And here’s a name,

and there! And as I was about to brush the moss from the name–

Look! an open hand engraved on the tombstone, the grave

of a kohen,

his fingers splayed in a spasm of holiness and blessing,

and here’s a grave concealed by a thicket of berries

that has to be brushed aside like a shock of hair

from the face of a beautiful beloved woman.

Historical information on the cemetery found here. This is the work of one Othmar Frühauf, who has photo-documented Jewish cemeteries in Germany for Alemannia Judaica (Both links are in German). My hat goes off to him.