>Freiberg is a pleasant small town in the state of Sachsen (Saxony), not far from Dresden. It has an old medieval wall and a pretty Altstadt, and a renowned Mining Academy. The locally made Nutcrackers, Christmas pyramids and other wooden figures are popular all over the world.

And, being within the former Deutsche Demokratische Republik, it has scars from both the Second World War and the Cold War, although they’re not immediately obvious. During a walk around the outskirts of town on Christmas Day , we stumbled upon a few of them.

The monument above is in the center of the Russian Cemetery, the resting place of Soviet soldiers who fell in battle.

The monument above is in the center of the Russian Cemetery, the resting place of Soviet soldiers who fell in battle.

Not far from it we found a smaller monument in memory of concentration camp victims. The letters KZ in a triangle at the top is the short form for Konzentrationslager. The text reads, Euch unsterbliche Opfer des Faschismus nie zu vergessen sei unsere Pflicht (It is our duty never to forget you, the immortal victims of fascism.)

Not far from it we found a smaller monument in memory of concentration camp victims. The letters KZ in a triangle at the top is the short form for Konzentrationslager. The text reads, Euch unsterbliche Opfer des Faschismus nie zu vergessen sei unsere Pflicht (It is our duty never to forget you, the immortal victims of fascism.)

We Americans tend to think of German concentration camps being exclusively for Jews, and of course they were the special targets of the Nazis. However, and especially in the early years of the Third Reich, just about anyone who didn’t fit into Hitler’s plans — communists, homosexuals, protesting clergy, pacifists, gypsies, criminals, outsiders — was threatened with incarceration and eventual execution. East Germany’s post-war government put special emphasis on the oppression of communists, obviously to keep their Soviet overlords happy, and also to help along the myth that there were no Nazis in the GDR.

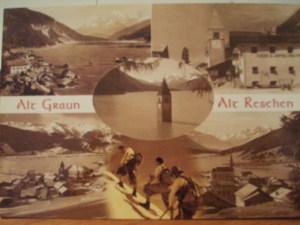

One block further down the hill we came to another kind of memorial — for the ethnic Germans, forced out of their homes in the east after the war, who died in the refugee camps at Freiberg. This was the final stop for 1,375 men, women and children from East Prussia, Pomerania, Silesia and Sudetenland, and they died of the usual refugee-related causes: injuries, hunger, cold, exhaustion.

One block further down the hill we came to another kind of memorial — for the ethnic Germans, forced out of their homes in the east after the war, who died in the refugee camps at Freiberg. This was the final stop for 1,375 men, women and children from East Prussia, Pomerania, Silesia and Sudetenland, and they died of the usual refugee-related causes: injuries, hunger, cold, exhaustion.

Again, I realize that the near-automatic response to this is often “They had it coming.” It is important to remember, however, that these Germans had been settled in those far-off regions for hundreds of years, and many of them had no more political connection to the Fatherland than did the Pennsylvania Dutch . They ended up being just another group of people to suffer from Hitler’s follies, if indirectly, but just as fatally.

I’ve been reading Anna Segher’s “Transit”, a novel set in Marseilles in 1940 and populated with all sorts of people fleeing the Nazi regime. Pushed to the coasts in front of the advancing German troops, they stand in all sorts of consular lines waiting for their visas — entry visas, exit visas, transit visas necessary for passing through one or more countries on route to another, places on board departing ships. One would wait for that last piece of paper with the official stamp from the proper authorities, only to get it after another had passed its expiration date.

Much of the book must have been taken from her own experiences and those of countless friends, as she fled Germany herself in 1933, first to France and then to Mexico. Much of what happened in her best-selling novel “The Seventh Cross” (later made into a film starring Spencer Tracey) came from information from camp escapees, as well pure speculation as to what was going on inside the Reich. Although she clearly didn’t know about the extent of the Holocaust while she was writing, she conveys quite well the minute-to-minute anxiety of being on the run in a paranoid, fearful country.

A dedicated enthusiast to the cause of a “better Germany”, Seghers moved to the East after the war and, like Brecht, was held up as an example of the literature of communist East Germany. “The Seventh Cross” was required reading in the schools. Naturally, I had never even heard of her.