> There is another circular hiking route around Bergisel, which is close by and not long. A nice walk, especially when you have to leave the house or go mad from the noise of jackhammers.

There is another circular hiking route around Bergisel, which is close by and not long. A nice walk, especially when you have to leave the house or go mad from the noise of jackhammers.

Blue-green, crystal clear, icy water. Beautiful, but the paths are narrow and slippery in the snow, and the place tried to kill me several times by nearly sending me down into the stream. My other route is more welcoming.

Blue-green, crystal clear, icy water. Beautiful, but the paths are narrow and slippery in the snow, and the place tried to kill me several times by nearly sending me down into the stream. My other route is more welcoming.

The back end of the Bergisel ski jump/cafe.

The back end of the Bergisel ski jump/cafe.

A memorial for Father Franz Reinisch, an Austrian priest who was executed by the Nazis in 1942 for refusing to join the Wehrmacht on conscientious grounds. He had spent his youth and student years in Innsbruck.

A memorial for Father Franz Reinisch, an Austrian priest who was executed by the Nazis in 1942 for refusing to join the Wehrmacht on conscientious grounds. He had spent his youth and student years in Innsbruck.

Category Archives: Mountains

>More Pagans In Tirol

> Yes, I know it look like a face in this photo, with a mouth full of pine needles, but that’s a trick of the shadows. There are at least a dozen cup marks in this stone, and they most certainly date back to the Bronze Age. There are various theories floating around as to what purpose these cup marks had. Maybe for ritual offerings, maybe for astronomical purposes or as pre-historic sign posts. Everyone has a theory, no one really knows. There is supposedly another stone nearby, one hill over from the altar mound at Goldbichl. For me it’s fascinating to think that these markings are from modern humans, with just as much intelligence potential as we have today, who lived here in these hills 6000 years ago, probably right where villages still exist today. And that this practice had spread all over Europe, from Merano to Northumberland. What was going on?

Yes, I know it look like a face in this photo, with a mouth full of pine needles, but that’s a trick of the shadows. There are at least a dozen cup marks in this stone, and they most certainly date back to the Bronze Age. There are various theories floating around as to what purpose these cup marks had. Maybe for ritual offerings, maybe for astronomical purposes or as pre-historic sign posts. Everyone has a theory, no one really knows. There is supposedly another stone nearby, one hill over from the altar mound at Goldbichl. For me it’s fascinating to think that these markings are from modern humans, with just as much intelligence potential as we have today, who lived here in these hills 6000 years ago, probably right where villages still exist today. And that this practice had spread all over Europe, from Merano to Northumberland. What was going on?

Further up the hill, the Lanser Moor, or Lans Marsh, a nature reserve.

Further up the hill, the Lanser Moor, or Lans Marsh, a nature reserve.

Nearby, the Lanser See, a popular swimming hole, deserted already. There’s a chill in the air now, even on sunny days, and swimming season is vorbei. A legend tells of a rich man who envied a farmer’s grove of trees, and took him to court to obtain it. The judge was unfair and the farmer lost his land, but not before he cursed it to sink under water. Which it did, and now we have the Lanser See to swim in.

Nearby, the Lanser See, a popular swimming hole, deserted already. There’s a chill in the air now, even on sunny days, and swimming season is vorbei. A legend tells of a rich man who envied a farmer’s grove of trees, and took him to court to obtain it. The judge was unfair and the farmer lost his land, but not before he cursed it to sink under water. Which it did, and now we have the Lanser See to swim in.

>Mountain Blogging: Achensee

> A day trip to the Achensee, a gorgeous lake in Tirol. It’s long and deep (133 meters) but the southern end is shallow and pale, a milky blue-green from the minerals (I think) in the sediment. The water is very clean, but milky to the point where you can’t see your feet when you stand knee-deep in it.

A day trip to the Achensee, a gorgeous lake in Tirol. It’s long and deep (133 meters) but the southern end is shallow and pale, a milky blue-green from the minerals (I think) in the sediment. The water is very clean, but milky to the point where you can’t see your feet when you stand knee-deep in it.

Beyond that point across the water, the lake turns northward, narrows and deepens significantly. There are several diving access points further north, and other villages. There is no road access to the west shore, but there are trails, and ferry service operates from May through October.

Beyond that point across the water, the lake turns northward, narrows and deepens significantly. There are several diving access points further north, and other villages. There is no road access to the west shore, but there are trails, and ferry service operates from May through October.

Seems it was perfect weather for paragliding, as there were dozens of them in the air, swooping around over the mountains, catching the currents. One landed practically at my feet as I approached the lake.

Seems it was perfect weather for paragliding, as there were dozens of them in the air, swooping around over the mountains, catching the currents. One landed practically at my feet as I approached the lake.

The Achenseebahn, a steep cog rail line which runs from Jenbach to the southernmost boat landing on the lake, was built in 1889 and still uses steam trains, unlike the chic and modern electrified Hungerburgbahn. I’ve ridden it once, it’s kind of fun, but it costs an arm and a leg (€22 one way!) I walked both ways (a good hour each way on the mountain biker’s forest road Via Bavarica Tyrolensis — don’t hog the road, give the bikers room to get past you, it’s their trail.)

The Achenseebahn, a steep cog rail line which runs from Jenbach to the southernmost boat landing on the lake, was built in 1889 and still uses steam trains, unlike the chic and modern electrified Hungerburgbahn. I’ve ridden it once, it’s kind of fun, but it costs an arm and a leg (€22 one way!) I walked both ways (a good hour each way on the mountain biker’s forest road Via Bavarica Tyrolensis — don’t hog the road, give the bikers room to get past you, it’s their trail.)

The villages around the Achensee are all about tourism now, and although they’ve kept it relatively tasteful, the area lacks the wild alpine feeling of other mountain lake regions. Here a bit of kitch near the walking path.

The villages around the Achensee are all about tourism now, and although they’ve kept it relatively tasteful, the area lacks the wild alpine feeling of other mountain lake regions. Here a bit of kitch near the walking path.

>Weekend Mountain Blogging: Wildblümchen

> I went out to look for an endangered flower called the Innsbrucker Küchenschellen, or Innsbruck Pasque Flower (Pulsatilla oenipontana,) for which there are areas set aside on the sunny slopes north of the town. This unusual flower only grows around here, being a hybrid from two other types of Pasque Flower, which happened to have a Tirolean rendez-vous. Being so particular about where it will and won’t grow, it’s facing extinction. The reserved areas above the villages of Arzl, Rum and Thaur and the tireless work of reasearchers is helping to keep that from happening.

I went out to look for an endangered flower called the Innsbrucker Küchenschellen, or Innsbruck Pasque Flower (Pulsatilla oenipontana,) for which there are areas set aside on the sunny slopes north of the town. This unusual flower only grows around here, being a hybrid from two other types of Pasque Flower, which happened to have a Tirolean rendez-vous. Being so particular about where it will and won’t grow, it’s facing extinction. The reserved areas above the villages of Arzl, Rum and Thaur and the tireless work of reasearchers is helping to keep that from happening.

Unfortunately, my timing was off, or they just bloomed early, because there was nothing but grass. It may also be so well hidden that I did not find the right spot. But here is a photo from the web:

Being up there, and having a sunny, free afternoon before me, I climbed up into the woods and followed the trails back toward Innsbruck via the Hungerburg. On the way I learned about a few more woodland wildflowers.

Being up there, and having a sunny, free afternoon before me, I climbed up into the woods and followed the trails back toward Innsbruck via the Hungerburg. On the way I learned about a few more woodland wildflowers.

Weisse Pestwurz, or Butterbur (Petasites albus), was growing right along the trail in shaded areas.

Weisse Pestwurz, or Butterbur (Petasites albus), was growing right along the trail in shaded areas.

A close relative of Butterbur is Huflattich, or Coltsfoot (Tussilago farfara), which, like Butterbur, has medicinal properties and is used to make cough suppressant.

A close relative of Butterbur is Huflattich, or Coltsfoot (Tussilago farfara), which, like Butterbur, has medicinal properties and is used to make cough suppressant.

One flower that’s certainly not about to die out is the Wood Anemone, which at this time of year covers a great deal of the forest floor. I found mostly violet colored flowers, but there were also many whites and a few dark pinks.

One flower that’s certainly not about to die out is the Wood Anemone, which at this time of year covers a great deal of the forest floor. I found mostly violet colored flowers, but there were also many whites and a few dark pinks.

A good place to find information on European wildflowers (in German):

http://waldwiesenblumen.gabathuler.org/index.php?alle=alle

>Weekend Mountain Blogging: Schloss Thaur

> There are so many “hidden” gems, right around Innsbruck, that most of the time you don’t even need public transportation to get to them. Yesterday I left my apartment and simply walked to the castle ruin above Thaur, a village in the hills beyond Innsbruck. It took about 2 hours. (I could have hopped on the bus to Thaur but it was a gorgeous day, perfect for a hike.)

There are so many “hidden” gems, right around Innsbruck, that most of the time you don’t even need public transportation to get to them. Yesterday I left my apartment and simply walked to the castle ruin above Thaur, a village in the hills beyond Innsbruck. It took about 2 hours. (I could have hopped on the bus to Thaur but it was a gorgeous day, perfect for a hike.)

The sketch above is from 1699, and according to the plaque on which I found it, is a “stylized version” of the Thaur Castle in its prime, which would have been around 1500. Some sections date back to 1200.

The sketch above is from 1699, and according to the plaque on which I found it, is a “stylized version” of the Thaur Castle in its prime, which would have been around 1500. Some sections date back to 1200.

Small theater productions are put on inside the ruins — if you put the audience in the open space in the center (ground level), there are lots of doorways, arches and upper levels for the actors to use. And of course a breathtaking view on which to gaze during the intermission.

Small theater productions are put on inside the ruins — if you put the audience in the open space in the center (ground level), there are lots of doorways, arches and upper levels for the actors to use. And of course a breathtaking view on which to gaze during the intermission.

On the way back, I took the Adoph-Pichler-Weg (I said PICHLER, Adolf Pichler — he was a native son, alpine geologist, teacher and author, and took part in the 1848 Revolutions.) This forest road doubles as a nature trail and leads all the way back to Innsbruck along the high ridge to the north, a nice trail with a gentle profile. I walked the entire way, but one could take this trail to the Hungerburg and then take either the Hungerburgbahn or the J Bus back into town.

On the way back, I took the Adoph-Pichler-Weg (I said PICHLER, Adolf Pichler — he was a native son, alpine geologist, teacher and author, and took part in the 1848 Revolutions.) This forest road doubles as a nature trail and leads all the way back to Innsbruck along the high ridge to the north, a nice trail with a gentle profile. I walked the entire way, but one could take this trail to the Hungerburg and then take either the Hungerburgbahn or the J Bus back into town.

>Long Before It Was Tirol, It Was Raetia

> This unassuming, wooded hill hides the remains of a group of Raetian houses from around 400 B.C.

This unassuming, wooded hill hides the remains of a group of Raetian houses from around 400 B.C.

The Raetians were a people who moved into the lands between Lake Garda and the Karwendel Mountains by the 6th century B.C. They are somehow associated with the Etruscans (their exact relationship is disputed, but there are similarities in their alphabets and a possible genetic link has come to light); Pliny the Elder wrote that they were an Etruscan clan driven out of the Po Valley by other tribes.

A technically and spiritually advanced society, they had a high level of technical, architectural and artisanal skills. Raetian wine from the area around Verona was Caesar Augustus’ preferred drink. They raised crops and farm animals such as cattle, sheep, goats and pigs. They kept dogs and horses. They handled in raisins, tree resin, lumber, wax, honey and cheese. They made their own artistically distinct ceramics.

What’s left of their houses are these stone cellars with narrow stair corridors. The entire group was in encircled by a sort of fort wall of sharpened logs, about one meter high (more picket fence than fortress)

What’s left of their houses are these stone cellars with narrow stair corridors. The entire group was in encircled by a sort of fort wall of sharpened logs, about one meter high (more picket fence than fortress)

Archaeologists have found much metalwork: chisels, axes, blades, iron rings, keys, door and chest handles, hooks. They families that lived here apparently did so in relative comfort, security and prosperity, able to make, trade for, or buy anything they needed.

Archaeologists have found much metalwork: chisels, axes, blades, iron rings, keys, door and chest handles, hooks. They families that lived here apparently did so in relative comfort, security and prosperity, able to make, trade for, or buy anything they needed.

And, all around, they had quite a view to enjoy —

Also found nearby (but no longer existent) was a temple area with sacrificial altars. In better times the Raetians sacrificed animals and crops to their god(s), and used the fire altars to sanctify bronze jewelry and weapons.

Also found nearby (but no longer existent) was a temple area with sacrificial altars. In better times the Raetians sacrificed animals and crops to their god(s), and used the fire altars to sanctify bronze jewelry and weapons.

In 15 B.C. the Romans decided to push northward, subjugating the Raetians and burning their villages. The survivors took to sacrificing coins, as everything else was too valuable to burn. And once the Romans forced their culture and language on everybody else, traces of the Raetians dried up.

The cellars are now preserved as a free open-air museum with signs posted giving information about the Raetians and about the archaeological finds, now on permanent exhibit at the Tiroler Landesmuseum in Innsbruck.

>A hike to the Lanser Kopf Flakstellungen

> A hike around the Paschberg, at the southern end Innsbruck. Looking back towards town, the Igler Bahn streetcar winds it way up through the forest to the villages on the plateau on the other side of the hill.

A hike around the Paschberg, at the southern end Innsbruck. Looking back towards town, the Igler Bahn streetcar winds it way up through the forest to the villages on the plateau on the other side of the hill.

One of the cutest houses around, the Tantegert stop. It’s a little fairy tale cottage along the tram line, and (I believe) inhabited by someone who works for the railroad. It’s nestled in the woods but not very private, with several hiking trails crossing right behind it.

One of the cutest houses around, the Tantegert stop. It’s a little fairy tale cottage along the tram line, and (I believe) inhabited by someone who works for the railroad. It’s nestled in the woods but not very private, with several hiking trails crossing right behind it.

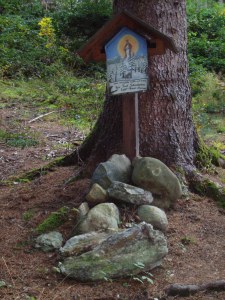

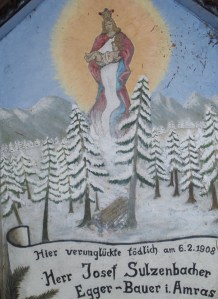

Not a grave, but a little shrine to someone who died at this spot on the hill. You see crosses and plaques like this, as well as tiny chapels, often in the mountains. What makes this one especially interesting is the painting which depicts the manner of the man’s death — it seems he fell, and his sled filled with firewood fell on top of him. I guess. Here’s a close up:

Not a grave, but a little shrine to someone who died at this spot on the hill. You see crosses and plaques like this, as well as tiny chapels, often in the mountains. What makes this one especially interesting is the painting which depicts the manner of the man’s death — it seems he fell, and his sled filled with firewood fell on top of him. I guess. Here’s a close up:

These concrete circles are at the very top of the Lanser Kopf, a rocky outcropping and the highest point on the hill. Remains from the Second World War, they were spots for anti-aircraft guns, or Flak. Did you know “Flak” stands for Fliegerabwehrkanone? As a child of peacetime, I never realized that talking about “getting flak for something” was of military origin, and German at that.

These concrete circles are at the very top of the Lanser Kopf, a rocky outcropping and the highest point on the hill. Remains from the Second World War, they were spots for anti-aircraft guns, or Flak. Did you know “Flak” stands for Fliegerabwehrkanone? As a child of peacetime, I never realized that talking about “getting flak for something” was of military origin, and German at that.

>Glacier First-Aid in Bavaria

>Part of the Schneeferner Glacier on the Zugspitz, Germany’s highest mountain, is getting a big white sunshade put over it for the summer months, to keep it from melting away entirely. The reason for this measure is not purely ecological, but also to help keep the ski slopes up there in business by saving a core section of the ice.

The tarps, 6000 square meters (nearly 65,000 square feet) in total, can be seen in a few photographs at this site (in German.) The Schneeferner has been shrinking considerably in the last 40 years; it is feared that the glacier may disappear by 2030.

>Weekend Mountain Blogging: Frau Hitt

> That jagged tooth-like rock jutting out of the middle of the North Ridge is known locally as Frau Hitt, the subject of an old tale. Frau Hitt was a giantess who, not being the generous sort, gave a beggar-woman only a stone to eat. The beggar turned out to be a witch, and promptly turned Frau Hitt and the horse she rode on into stone, and her farmlands into barren, rocky peaks.

That jagged tooth-like rock jutting out of the middle of the North Ridge is known locally as Frau Hitt, the subject of an old tale. Frau Hitt was a giantess who, not being the generous sort, gave a beggar-woman only a stone to eat. The beggar turned out to be a witch, and promptly turned Frau Hitt and the horse she rode on into stone, and her farmlands into barren, rocky peaks.

She’s a favorite destination of mountain climbers looking for an afternoon climb.

>Banana trees on the ski slopes

>Achim Steiner, executive director of the United Nations Environment Program, said today that the world’s glaciers are melting “at an alarming rate”, based on data collected by the World Glacier Monitoring Service in Zurich.

Juliette Jowit from the Observer writes:

Glaciers act like gigantic water towers: snow falls on the top in wet seasons, where it freezes and compacts over years, while melting water at the bottom is released gradually, keeping rivers flowing even in the hottest weather. ‘Glaciers are like a bank,’ says Professor Wilfried Haeberli, director of the World Glacier Monitoring Service. ‘You have income – mainly snow – and you have expenditure – mainly melting: the difference between snowfall and melting is the yearly balance.’

Since at least 1980 the service has kept a constant record of this net gain or loss in mass balance of 30 ‘reference’ glaciers in nine mountain ranges around the world. It has also used travellers’ diaries, photographs, and the clues left on landscapes scarred by the moving mass of ice and debris to map historic growth and the gradual decline of glaciers since the mid-19th century.

From 1850 to 1970, the team estimates net losses averaged about 30cm a year; between 1970 to 2000 they rose to 60-90cm a year; and since 2000 the average has been more than one metre a year. Last year the total net loss was the biggest ever, 1.3m, and only one glacier became larger. Worldwide, the vast majority of the planet’s 160,000 glaciers are receding, ‘at least’ as much as this, says Haeberli, probably more – a claim supported by evidence from around the world.

In North America, Dr Bruce Molina of the US Geological Survey says that in Alaska ’99-plus per cent of glaciers are retreating or stagnating’.

In the European Alps, a report last year by UNEP said glaciers declined, from a peak in the 1850s, by 35 per cent by 1970 and by 50 per cent by 2000, and lost 5-10 per cent in the mega-hot year of 2003 alone.

UNEP has also reported declines in the last 50-150 years of 1.3 per cent in the Arctic islands to 50 per cent in the North Caucasus in Russia, 25-50 per cent in central Asia, a 2km retreat of the massive Gangotri glacier which feeds the Ganges, 49 to 61 per cent in New Zealand, and 80 per cent in the high mountains of southern Africa. There is also ‘considerable’ shrinking of medium and small glaciers in central Chile and Argentina accompanied by ‘drastic retreat’ of glaciers in Patagonia to the south.

Steiner also mentioned that the Climate Conference to be held in 2009 in Copenhagen “will provide the true litmus test of governments’ commitment to reducing greenhouse gas emissions, the carbon pollution from fossil fuels damaging Earth’s climate system.

Otherwise, and like the glaciers, our room for manoeuvre and the opportunity to act may simply melt away.”