> Here’s something I contemplated blogging about for a while. Several years ago, when I’d first moved to Innsbruck, I set out one afternoon on a little day hike, hoping to find the name and location of a particularly pretty duet of onion-dome church towers which I could see from my window. From my hiking map it was difficult to figure out just how far away they might be, and I ended up overshooting and headed toward the hills above the next town over. Not knowing the name of the church, I looked for a “+” symbol on the map (signifying a chapel), and went for the one which looked like it might be in the right place. The area was called Judenstein.

Here’s something I contemplated blogging about for a while. Several years ago, when I’d first moved to Innsbruck, I set out one afternoon on a little day hike, hoping to find the name and location of a particularly pretty duet of onion-dome church towers which I could see from my window. From my hiking map it was difficult to figure out just how far away they might be, and I ended up overshooting and headed toward the hills above the next town over. Not knowing the name of the church, I looked for a “+” symbol on the map (signifying a chapel), and went for the one which looked like it might be in the right place. The area was called Judenstein.  It wasn’t the chapel I was looking for, but it turned out to be much more interesting. The church at Judenstein has a history. The story goes like this: in 1462 (or so) a three-year-old boy named Anderl (diminutive for Andreas) Oxner went missing from his village. His body was found later, in the area. (This much might be true.) Roughly a hundred and fifty years later, a counter-reformationist and anti-Semite named named Hippolyt Guarinoni invented a story about Anderl’s death which he modeled after a popular story going around at the time involving a little boy named Simon in the city of Trent (as in the Council of Trent.) In Guarinoni’s new fable, traveling Jewish merchants bought the boy from his stepfather, then performed a ritual murder, cutting his throat open and collecting the blood. Guarinoni got a lot of traction out of this story, and with it built a church on the scene of the alleged crime and started up a cult venerating the “martyred” child. On top of this the Brothers Grimm picked up the story and took it all over Europe, if not the world, in their tale “Der Judenstein” (The Jews’ Stone).

It wasn’t the chapel I was looking for, but it turned out to be much more interesting. The church at Judenstein has a history. The story goes like this: in 1462 (or so) a three-year-old boy named Anderl (diminutive for Andreas) Oxner went missing from his village. His body was found later, in the area. (This much might be true.) Roughly a hundred and fifty years later, a counter-reformationist and anti-Semite named named Hippolyt Guarinoni invented a story about Anderl’s death which he modeled after a popular story going around at the time involving a little boy named Simon in the city of Trent (as in the Council of Trent.) In Guarinoni’s new fable, traveling Jewish merchants bought the boy from his stepfather, then performed a ritual murder, cutting his throat open and collecting the blood. Guarinoni got a lot of traction out of this story, and with it built a church on the scene of the alleged crime and started up a cult venerating the “martyred” child. On top of this the Brothers Grimm picked up the story and took it all over Europe, if not the world, in their tale “Der Judenstein” (The Jews’ Stone).  The little church, while quite lovely, has frescos on the ceiling depicting the disappearance of Anderl (one shows the grief of his mother when, while working in the fields, she learns of her son’s death). If you visit this church the one fresco you will NOT see is the one which was (thankfully) painted over — depicting little Anderl actually being cut open by Jewish men. I kid you not, I wish I were.

The little church, while quite lovely, has frescos on the ceiling depicting the disappearance of Anderl (one shows the grief of his mother when, while working in the fields, she learns of her son’s death). If you visit this church the one fresco you will NOT see is the one which was (thankfully) painted over — depicting little Anderl actually being cut open by Jewish men. I kid you not, I wish I were.  I need to point out that, while the Roman Catholic church was instrumental in this kind of story gaining traction to begin with, in 1953 Paul Rusch, then Bishop of Innsbruck, struck the holiday commemorating Anderl’s “martyrdom” from the church calendar. In the 1980s Bishop Reinhold Stecher began to dismantle the cult by having Anderl’s bones removed from the altar, ordering the offending fresco to be painted over, and officially banning the cult from the church (in the 1990s). There is now a plaque inside the church explaining the myth and it’s falsehood. Problem was, by that time Anderl’s fans were not to be dissuaded — the annual pilgrimages occur every July on Anderl’s “day”, hosted privately (i.e. not through the Church) by various right wing extreme factions and Catholic fundamentalists. Tirol’s anti-Semitic and anti-other roots are complicated — more religious than racial, reflecting the fear of outsiders often encountered in mountain people, and encouraged by the church (right there alongside hatred toward heretics and Protestants) by calling Jews Christ-killers and all that other fun stuff. Then the Nazis took over and took things to extremes. Today, religion plays little part in the local bigotry. The right-wingers tend to harp on “preserving our way of life and our culture”, and work on keeping brown people and Slavs out. (Note to the BZÖ: It’s not working.) The right-leaning view Turks and other eastern European nationals today much in the same way American wingnuts view Mexican and Central American immigrants to the U.S. At the turn of the last century, even Italians were suspect. I know of a family who won’t talk to one of their daughters because she married a German. And another who can’t accept their daughter-in-law, for the crime of being (gasp) Swiss. I am speaking of things I have heard and personally learned, not of Tiroleans in general — there are lots of friendly and open-minded people here too, especially in the cities but out in the countryside as well. But things like this, the stuff not talked about, are embedded in the culture.

I need to point out that, while the Roman Catholic church was instrumental in this kind of story gaining traction to begin with, in 1953 Paul Rusch, then Bishop of Innsbruck, struck the holiday commemorating Anderl’s “martyrdom” from the church calendar. In the 1980s Bishop Reinhold Stecher began to dismantle the cult by having Anderl’s bones removed from the altar, ordering the offending fresco to be painted over, and officially banning the cult from the church (in the 1990s). There is now a plaque inside the church explaining the myth and it’s falsehood. Problem was, by that time Anderl’s fans were not to be dissuaded — the annual pilgrimages occur every July on Anderl’s “day”, hosted privately (i.e. not through the Church) by various right wing extreme factions and Catholic fundamentalists. Tirol’s anti-Semitic and anti-other roots are complicated — more religious than racial, reflecting the fear of outsiders often encountered in mountain people, and encouraged by the church (right there alongside hatred toward heretics and Protestants) by calling Jews Christ-killers and all that other fun stuff. Then the Nazis took over and took things to extremes. Today, religion plays little part in the local bigotry. The right-wingers tend to harp on “preserving our way of life and our culture”, and work on keeping brown people and Slavs out. (Note to the BZÖ: It’s not working.) The right-leaning view Turks and other eastern European nationals today much in the same way American wingnuts view Mexican and Central American immigrants to the U.S. At the turn of the last century, even Italians were suspect. I know of a family who won’t talk to one of their daughters because she married a German. And another who can’t accept their daughter-in-law, for the crime of being (gasp) Swiss. I am speaking of things I have heard and personally learned, not of Tiroleans in general — there are lots of friendly and open-minded people here too, especially in the cities but out in the countryside as well. But things like this, the stuff not talked about, are embedded in the culture.

UPDATE: (16 February 2011): I have come across a book about pre-Christian finds in Austria, which has this to say about the Judenstein (translated here by me):

The “Judenstein” was without a doubt once an altar, where people had been once ritually sacrificed… According to the legend, after the murder, the Jews hung the boy from a birch tree. “That is a purely Heathen story, nothing Christian nor Jewish in it”, writes Norbert Mantl in his 1967 book about pre-Christian cult relics in the Upper Inn Valley. “The saga deals with the memory of an ages-old fertility sacrifice whose ritual is still recognizable. Blood was spilled over the stone and the birch, representing all plant life necessary to humans, receiving the corpse as an offering. It had to do with fertility and a good harvest, but also for the welfare and prosperity of humans and their animals.”

So it is possible that the story did not get made up out of thin air, but was a contorted version of a much older “enemy” of the church, refitted for the Middle Ages.

There are so many “hidden” gems, right around Innsbruck, that most of the time you don’t even need public transportation to get to them. Yesterday I left my apartment and simply walked to the castle ruin above Thaur, a village in the hills beyond Innsbruck. It took about 2 hours. (I could have hopped on the bus to Thaur but it was a gorgeous day, perfect for a hike.)

There are so many “hidden” gems, right around Innsbruck, that most of the time you don’t even need public transportation to get to them. Yesterday I left my apartment and simply walked to the castle ruin above Thaur, a village in the hills beyond Innsbruck. It took about 2 hours. (I could have hopped on the bus to Thaur but it was a gorgeous day, perfect for a hike.) The sketch above is from 1699, and according to the plaque on which I found it, is a “stylized version” of the Thaur Castle in its prime, which would have been around 1500. Some sections date back to 1200.

The sketch above is from 1699, and according to the plaque on which I found it, is a “stylized version” of the Thaur Castle in its prime, which would have been around 1500. Some sections date back to 1200.

Small theater productions are put on inside the ruins — if you put the audience in the open space in the center (ground level), there are lots of doorways, arches and upper levels for the actors to use. And of course a breathtaking view on which to gaze during the intermission.

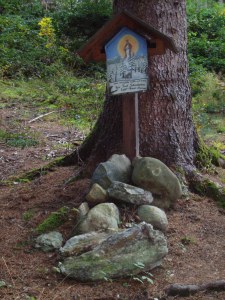

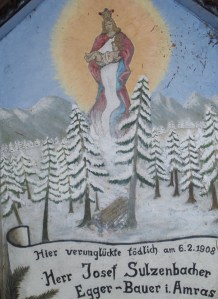

Small theater productions are put on inside the ruins — if you put the audience in the open space in the center (ground level), there are lots of doorways, arches and upper levels for the actors to use. And of course a breathtaking view on which to gaze during the intermission. On the way back, I took the Adoph-Pichler-Weg (I said PICHLER, Adolf Pichler — he was a native son, alpine geologist, teacher and author, and took part in the 1848 Revolutions.) This forest road doubles as a nature trail and leads all the way back to Innsbruck along the high ridge to the north, a nice trail with a gentle profile. I walked the entire way, but one could take this trail to the Hungerburg and then take either the Hungerburgbahn or the J Bus back into town.

On the way back, I took the Adoph-Pichler-Weg (I said PICHLER, Adolf Pichler — he was a native son, alpine geologist, teacher and author, and took part in the 1848 Revolutions.) This forest road doubles as a nature trail and leads all the way back to Innsbruck along the high ridge to the north, a nice trail with a gentle profile. I walked the entire way, but one could take this trail to the Hungerburg and then take either the Hungerburgbahn or the J Bus back into town.