(Source: Bing Maps)

Fellow blogger Zeitspringer recently bemoaned the fact that the sacrificial burning site in Gauting, Bavaria, has little information about it posted in the Web, and nothing at the site itself, and contrasts that lack of information with the excellent resources about the Goldbichl here in Tirol. While he is right to wish for more in Bavaria, I offer up here a similar site which has been all but forgotten, on the large hill here known as Bergisel.

Bergisel is known today as the site of one of the “Four Hills” ski jumps (and a very nice one at that). Historically, it’s connected with Andreas Hofer and the battles fought there in the early 1800s, and as the location of the new Tirol Panorama Museum. There is also a pretty trail along the Sill Gorge, on the back side of the hill. But there are other interesting things about it.

Bergisel was in fact known to be a significant archaeological site, if at first only the northern spur, since at least the 1840s. The partial collection of a large treasure find is housed in the Tirol State Museum Ferdinandeum, the other part having been “carried off by the wagonful and sold by weight to bellmakers.” The exact location of the discovery was not given, however the most likely place is the current site of the Kaiserjäger Museum, as that was the only area where extensive digging and construction had been conducted at the time.

Deposits of ritual offerings have been found in other parts of the Alps, for example in nearby Fliess, west of Innsbruck. These offerings were destroyed, smashed, bent or cut into pieces, but are rarely found with burn marks. In Ancient Greece, cult images were draped with fabrics which had to be replaced periodically. Holy apparel and it’s trimmings, such as metal clasps, could not simply be thrown out, and so chambers were dug into the earth on or near sacred ground, where these items could be deposited. A tour around the early history exhibits in the basement of the Ferdinandeum will show a large number of these clasps having been found all over Tirol, which points to a similar practice. Also — in prehistoric graves found north of the Alps, the dead were outfitted in their finest, including metal objects such as clasps and armbands. The inhabitants of Tirol did not do this, which leads to the idea that their belongings were then offered to their deities for the common good.

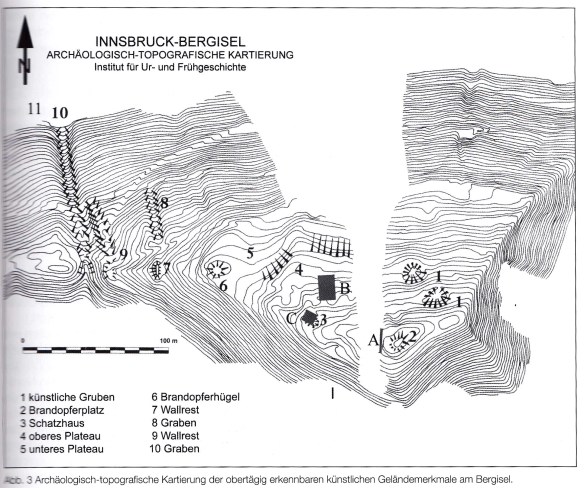

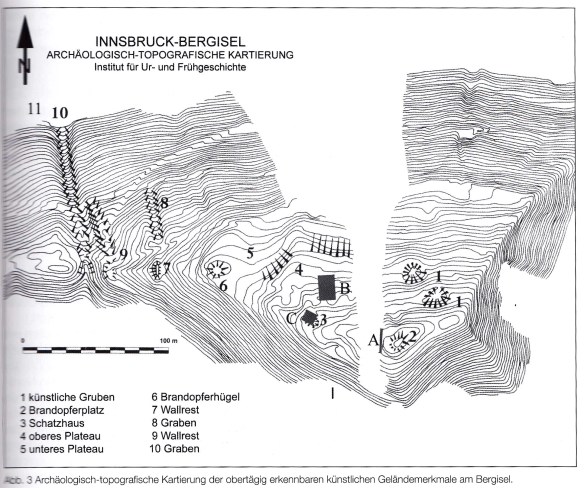

(Source: “Ur- und Frühgeschichte von Innsbruck”, Katalog zur Ausstellung im Tiroler Landesmuseum Ferdinandeum 2007.)

More recent excavations (between the demolition of the old ski jump in 2001, and the construction of the new one) have uncovered a site for burnt offerings near the highest point of the hill, just a few meters east of the ski jump tower. Animal bones were found which had been burnt at a temperature of over 600°C. Of course when the old jump was built in the 1960s, a large swath of earth had been removed, and a great deal of archaeological evidence went with it. But the eastern side seems to be relatively intact, and awaiting additional future, as-of-yet unplanned excavations. The articles found have been dated to as early as 650 BC to as late as 15 BC, when the Romans arrived.

This information is all public, either via the internet or from Ferdinandeum publications such as the one named above. However, there is absolutely NO information at the site itself. There are barely trails — practically dog paths — up the steep grades. I only made it up (and down) by grabbing onto tree roots and watching very carefully where I stepped. Autumn’s leaves, needles and pine cones added a certain slipperiness to the adventure. (The sites, such as they are, are on the outside of the fenced-in ski jump area, so you can’t just take the incline.)

The altar mound as seen today, on the highest point of the hill.

The fence around the sport area runs through the mound, which seems a little unfortunate. Below: the man-made terraces on the north side of the hill, found above the old shooting range. Evidence of housing (from different eras) was unearthed on them, possibly for whomever tended to the holy sites.

In the museum book, it is noted in summary that no other area of excavation in central Europe has revealed so much sacred activity — the Raetians, from the evidence found, seemed to have devoted more of their time to religious rites than any other tribe, and for over 600 years.