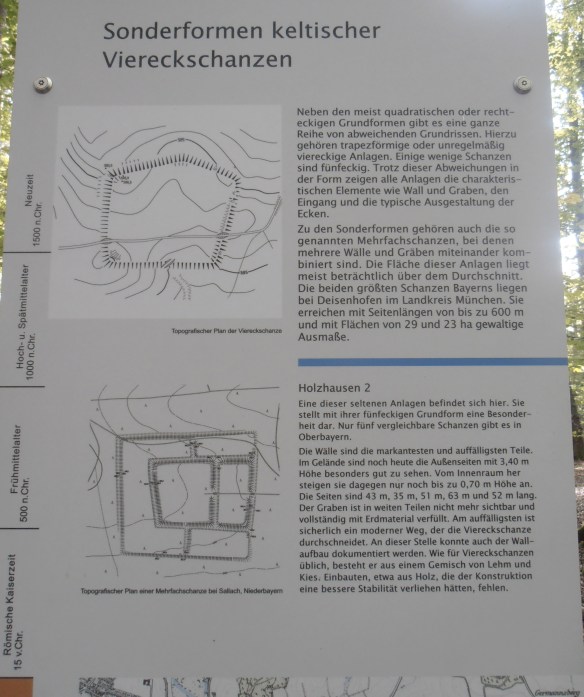

Along with the Sunderburg and the pre-Christian grave mounds hidden here and there, the area immediately north of the Ammersee also contains two fairly well-preserved Celtic Viereckschanzen, rectangular earthen enclosures, called Holzhausen 1 and 2. Their function is disputed among archaeologists as to whether they held sacred groves or were built for more practical purposes as forerunners to medieval city walls. They were certainly large enough for whole clans to live in them, being roughly 100 meters long and 75 meters wide, which would make for an unusually wide football field.

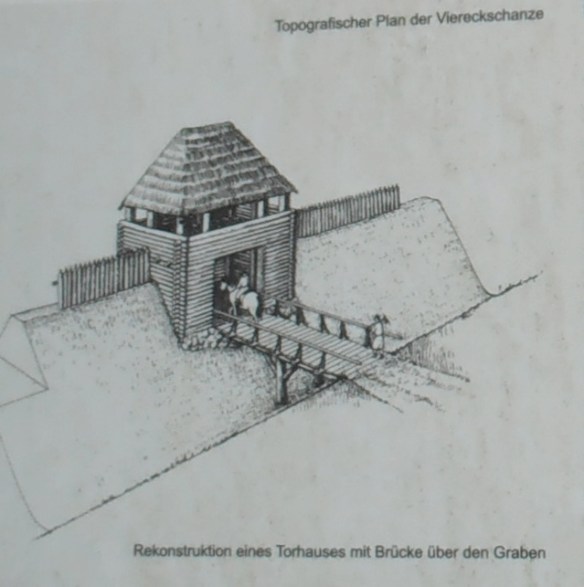

Holzhausen 1 has an entrance gate, or at least a higher break in the wall where a gate would have been built. A nearby sign suggests how one would have looked.

A path now leads along the top of the wall, bringing the visitor all the way around and back to the gate.

Inside the wall is meadow, and, interestingly, a small copse of young trees about right in the middle. Much older trees had stood here but had been cut down. We didn’t count the rings in their stumps but there were many. Possibly someone is maintaining their own sacred grove.

At Holzhausen 2, the forest has taken over. The ground inside the wall has filled in over time so that the earthwork is now more of a plateau. Here is the edge, from above on the wall.

Here again, just about in the middle of the Schanze, an unusual circle of plant life. I’m going to assume that fires were made here in the recent past, and the wood ash left the earth especially fertile for this plant. I’m not very romantic about the past — I tend to think people had way too much to do trying to stay alive and healthy and keep what they had, than to put all this work into a little sacred circle. But hey, that’s me. It’s clearly someone’s sacred circle now, and it’s nice to know that these someones are caring for this speck of land.

By each Schanze is a small sign explaining the site, and nothing more. Better that way — it’s not easy to find, not easy to reach (we took our mountain bikes), and less liable to be wrecked. Holzhausen is just south of Fürstenfeldbruck, near Schöngeising, 40 kilometers west of Munich.