>Part of the Schneeferner Glacier on the Zugspitz, Germany’s highest mountain, is getting a big white sunshade put over it for the summer months, to keep it from melting away entirely. The reason for this measure is not purely ecological, but also to help keep the ski slopes up there in business by saving a core section of the ice.

The tarps, 6000 square meters (nearly 65,000 square feet) in total, can be seen in a few photographs at this site (in German.) The Schneeferner has been shrinking considerably in the last 40 years; it is feared that the glacier may disappear by 2030.

Author Archives: kcosumano

>Four Catholic priests from Tirol and Vorarlberg

>From a booklet* I came across while visiting a village church. I’m not much into organized religion but since organized religion isn’t forcing me to live their way, I don’t hold anything against it.

That said, as all personal (and especially local) stories out of the time of the Third Reich interest me, I am passing these along. Four individuals is not much of a resistance in the time of Cardinal Innitzer, who, despite having said publicly that “There is only one Führer: Jesus Christ”, seemed to bend over backward to make the Nazis feel at home in Vienna. One assumes there were many others who simply kept their heads low, and others who used the political situation to their own benefit. Probably there were many who started out in vocal opposition, but then got a stiff warning (such as a few years at Buchenwald or Dachau) and stayed quiet for the duration of the Reich. These four priests did not quiet down, even under intense pressure to do so. For that, they paid with their lives.

Born, raised and ordained as a priest in Tirol, Neururer was working in the village of Götzens near Innsbruck when Hitler took over Austria. Probably watched carefully due to his activities with the Christian Social Movement, but brought in for “slander to the detriment of German marriage” when he advised a Tirolean woman against marrying a divorced man (who happened to be a Nazi and a friend of the Gauleiter.) Sent to Dachau, then Buchenwald. At Buchenwald in 1940 he baptized a fellow inmate, and was found out. He was hanged upside down from chains until he died, 34 hours later.

From Tirol, ordained in Fribourg, Switzerland. Worked in Graz until the Anschluss, when his superiors sent him home to Tirol, hoping to avoid problems. He continued however, to speak out against Hitler, was banned from teaching, and urged to leave the country. The Gestapo followed him to Spain, and two agents posing as exiled Jews seeking catholic instruction befriended him and managed to get him over the border into Nazi-occupied France, where he was promptly arrested. He was brought to Berlin, and was tried and beheaded in 1943.

Carl Lampert

From Vorarlberg, ordained and active in Tirol. Remained an outspoken protester of National Socialist church policy despite several arrests, and time at Dachau and Sachenhausen concentration camps. Released in 1941 and moved to northern Germany, he was brought in again on charges of treason, spying, disrupting the war effort, consorting with the enemy and listening to foreign radio broadcasts (this last charge alone was punishable by death.) He was sentenced to death and beheaded in 1944.

Franz Reinisch (link in German)

Also from Vorlarberg, Reinisch was able to steer clear of the Nazis during his young career (he spent time studying law and then theology into the 30s), but was banned from speaking publicly by the Gestapo in 1940. He continued work in the church as a translator, in 1941 called up to the Wehrmacht, which includes a mandatory oath of allegiance to Hitler. This he refused to do, knowing it meant certain death. In 1942 he was arrested, tried, convicted and beheaded.

* Bischöfliches Priesterseminar Innsbruck-Feldkirch Heft 101 — Sommersemester 2008

>Reith bei Seefeld

>The Mittenwaldbahn (a railway to Munich which goes through some splendid mountain scenery, and I do mean through — it’s all bridges and tunnels til Bavaria) stops in the village of Reith bei Seefeld, which claims a cultural walking tour of sorts through it and its neighboring village, Leithen. Some of it was the usual, chapels and Madonnas, but a few items were interesting.

Reith saw its share of suffering from the World Wars — from the two wars it lost 28 men, which doesn’t sound like much until you remember how small this village is. Then in 1945 the Allies bombed it six times, dropping 300 bombs in attempts to destroy the rail line. This is an Allied bombshell from the time. (Note: Tirol was occupied by British forces after the war.)

Reith saw its share of suffering from the World Wars — from the two wars it lost 28 men, which doesn’t sound like much until you remember how small this village is. Then in 1945 the Allies bombed it six times, dropping 300 bombs in attempts to destroy the rail line. This is an Allied bombshell from the time. (Note: Tirol was occupied by British forces after the war.)

In Leithen one finds the alleged birthplace of Thyrsus, a 9th-century giant known for being killed by the more-famous Haymon the Giant, who regretted the act enough to build the collegiate church in Wilten. Historical researchers presume that Haymon was a Bavarian aristocrat with neighbor issues; so far I found no light on who Thyrsus really was. He’s the one on the right in this fresco. The saga relates that when Thyrus was slayed, his blood spilled into the ground and became oil shale, as indeed there are shale deposits in the region around Seefeld and Scharnitz.

In Leithen one finds the alleged birthplace of Thyrsus, a 9th-century giant known for being killed by the more-famous Haymon the Giant, who regretted the act enough to build the collegiate church in Wilten. Historical researchers presume that Haymon was a Bavarian aristocrat with neighbor issues; so far I found no light on who Thyrsus really was. He’s the one on the right in this fresco. The saga relates that when Thyrus was slayed, his blood spilled into the ground and became oil shale, as indeed there are shale deposits in the region around Seefeld and Scharnitz.

The Thirty Years’ War brought the Plague to Tirol. A wealthy Innsbruck merchant fled with his family to Leithen and fell ill there, but pledged to built this pillar, painted with scenes from the crucifixion, which he did in 1637. Often one finds not just a pillar but an entire church built out of gratitude for someone’s survival. Evidently many people made a lot of deals with God in the hopes of surviving the Plague, as Pestkirchen are abundant — in fact, there’s one at the end of my street.

The Thirty Years’ War brought the Plague to Tirol. A wealthy Innsbruck merchant fled with his family to Leithen and fell ill there, but pledged to built this pillar, painted with scenes from the crucifixion, which he did in 1637. Often one finds not just a pillar but an entire church built out of gratitude for someone’s survival. Evidently many people made a lot of deals with God in the hopes of surviving the Plague, as Pestkirchen are abundant — in fact, there’s one at the end of my street.

This rock sticking out of the ground would probably have escaped notice completely if not for the list of monuments found on the walking tour, which I picked up at the tourist information desk. It was once a milestone, with the figure of St. Nicholas (Reith’s patron saint) attached to the base. In 1703 Bavarian soldiers (in the War of Spanish Succession) sacked the village and ripped out the saint. Ever since, the base has stood there as a memorial (to what, I’m not sure. Possibly as a reminder to hate the Germans and the French.)

This rock sticking out of the ground would probably have escaped notice completely if not for the list of monuments found on the walking tour, which I picked up at the tourist information desk. It was once a milestone, with the figure of St. Nicholas (Reith’s patron saint) attached to the base. In 1703 Bavarian soldiers (in the War of Spanish Succession) sacked the village and ripped out the saint. Ever since, the base has stood there as a memorial (to what, I’m not sure. Possibly as a reminder to hate the Germans and the French.)

So, the general consensus seems to be that there was a lot of fighting going on, just like anywhere. Centuries of peaceful co-existence, then something happens, blood is shed. And humans memorialize it afterward, as best they can.

>Speaking About The Past

>Visited a Saturday morning flea market in the Altstadt last weekend, picked up some used books, including one out-of-print book titled “Man muß darüber reden” (“One Must Speak About It”), a collection of talks given by Nazi concentration camp survivors to classes of schoolchildren (high school age, one assumes, since the stories are pretty detailed) in the 1970s-80s. The book is really an interesting read, not only for the survivors’ stories, but for the questions asked by the pupils — sometimes naive, sometimes incredibly direct, and often questions that an adult would not be able to bring him- or herself to ask out loud.

For me, there was something new in the stories of how they came home after the war — and I find this is a big hole in my knowledge of the holocaust. How did people get home, did they have any help. how were they treated by their neighbors, was anything said about the past? And, the biggest question for me, why did they return to their homes, and not emigrate to other coutries, like many others? Some of the speakers in the book were Jewish, some had been Communists or otherwise politically active somehow against the Nazis, some were simply unlucky. They all, each and every one, spoke of how it was luck that enabled them to survive — luck and solidarity among the inmates, although solidarity alone didn’t help millions of others.

According to some accompanying words from a government minister at the back of the book, these talks are now a regular part of the school experience in Austria. I don’t know if that’s still true, given that the ages of survivors must be fairly advanced now. I need to ask some of my home-grown friends about it.

One often hears that Austrians have not come to terms with its Nazi past, and that may be true but it’s not for lack of effort by liberal-thinking people. There have been steps, small steps, all along the way. They are not always easy to see, especially by us Ausländer who see the xenophobic side of society often enough. But it’s most definitely part of The Discussion, and that offers hope.

>Mein Freund Der Baum Ist Tod

>

An enormous old tree across the street had been taken down early this morning. It had probably succumbed from the construction work on the underground garage, or maybe city life had just taken its toll on it. Telling my beau about it on the telephone, he was reminded of a 1960s pop song, one of his mother’s favorites, the refrain being “My friend the tree is dead, it fell in the early morning dawn.” The lyrics describe how a favorite tree has been felled to make room for a new modern building — sort of a German “Big Yellow Taxi”.

So I looked up the song and the singer, Alexandra, and found she’d had quite an interesting, if short, life. Born in a German area of Lithuania, expelled with other Germans after the war, married briefly at 19 to a Russian 30 years her senior, also performed songs in French, English, Russian and Hebrew, had a love affair with a Cold War spy, died under mysterious circumstances at the age of 26. Here is her Wikipedia entry and the song clip.

>Discussing racism, back in the 1920s

> My grandfather died before I was born, and my grandmother then married a widower in town who had been lucky enough to have married a woman with family money the first time around. This means that my grandmother, having been born in working-class immigrant circumstances, spent the last 50 years of her life (she almost made it to 92) in a lovely woodland cottage with very nice antique furniture and heirloom jewelry.

My grandfather died before I was born, and my grandmother then married a widower in town who had been lucky enough to have married a woman with family money the first time around. This means that my grandmother, having been born in working-class immigrant circumstances, spent the last 50 years of her life (she almost made it to 92) in a lovely woodland cottage with very nice antique furniture and heirloom jewelry.

The cottage had once been part of a private club, started in 1920 when a group of people bought up several acres of woodland and built summer bungalows there, presumably to drink in peace (during Prohibition) as well as enjoy the country air. The club had disbanded for good some 30 years ago, and the lots were divided up and claimed by their current occupants. When my grandmother died and we took possession of her papers, we found quite a bit pertaining to the club, some of it quite old.

One of the most interesting from this archive is a letter dated August 11, 1926 and written by a club member to one of its officers. I quote the body of the letter in its entirety:

Dear Bob: Because of important business engagements Tues. the 11th I shall be unable to attend a meeting of [ ] Club. Since my talk with you I realize that most items to be discussed at the meeting have to do with actions of mine I regret that I cannot be present. Shall try to make my position clear therefore in this letter.

I am now aware of the animosity towards me since I moved to [ ] and brought Percy over to the unoccupied house because I wanted to make it easy for him to take care of the horses and the work about the bungalow. When I mentioned the fact that I wanted to fix up the house for him I certainly did not try in any way to mislead anyone as to his color — that evidently being the main objection to him. Am only sorry that I did not get to the Club meetings to as to bring it before all the members.

It became my unpleasant duty on the strength of the objections made to him going in swimming with some of his friends to ask him to keep from doing it in the future. He assured me he would not give any case for complaint in the future.

Perhaps I am prejudiced in Percy’s favor, but I feel I have done him an unintentional wrong — stirred up in him a feeling of bitterness because of this evident dislike to his color. We have appreciated him so much and have noted the whiteness of his character — that it has really spoiled our desire to stay here.

As soon as we can dispose of the horses which we are now trying to do Percy intends moving back to town and when necessary repairs are made to our home in town we shall also be going over. This will possibly be the end of August.

Would appreciate having a statement of what I owe the Club so that prompt settlement may be made.

Cordially yours,

I find this letter a fascinating glimpse into the prevailing attitudes about race in the 1920s, including the well-meaning racism of the writer — he seems to have had his heart in the right place, yet he refers to his employee only by his first name, and refers to the “whiteness of his character”. I do not hold this against him — this was, after all, 1926. It’s just interesting to me. What do you think? — Comments are welcome.

>”Soldatenfriedhof” am Domplatz

> The Cathedral has a few special installations for Lent, including this “soldiers’ cemetery” of wooden crosses out in the little park in the Domplatz, by the artist Franz Wassermann. The 200 crosses bear the words “My body doesn’t belong to me”, “My body is a weapon” and “My body is a battlefield”, in 6 languages including Latin, Hebrew and Arabic.

The Cathedral has a few special installations for Lent, including this “soldiers’ cemetery” of wooden crosses out in the little park in the Domplatz, by the artist Franz Wassermann. The 200 crosses bear the words “My body doesn’t belong to me”, “My body is a weapon” and “My body is a battlefield”, in 6 languages including Latin, Hebrew and Arabic.

Also part of the installation are the six large flags hanging from the neighboring buildings, bearing anonymous portraits. Their intention is to remind one of the “abuse of religion, church, business and politics for nationalist purposes.” According to the Cathedral’s website, the idea is to provoke thoughts about the inhumanity of war especially now, in this 200th anniversary year of Tirolean Freedom Fighters.

>Judenstein, or The Jews’ Stone

> Here’s something I contemplated blogging about for a while. Several years ago, when I’d first moved to Innsbruck, I set out one afternoon on a little day hike, hoping to find the name and location of a particularly pretty duet of onion-dome church towers which I could see from my window. From my hiking map it was difficult to figure out just how far away they might be, and I ended up overshooting and headed toward the hills above the next town over. Not knowing the name of the church, I looked for a “+” symbol on the map (signifying a chapel), and went for the one which looked like it might be in the right place. The area was called Judenstein.

Here’s something I contemplated blogging about for a while. Several years ago, when I’d first moved to Innsbruck, I set out one afternoon on a little day hike, hoping to find the name and location of a particularly pretty duet of onion-dome church towers which I could see from my window. From my hiking map it was difficult to figure out just how far away they might be, and I ended up overshooting and headed toward the hills above the next town over. Not knowing the name of the church, I looked for a “+” symbol on the map (signifying a chapel), and went for the one which looked like it might be in the right place. The area was called Judenstein.  It wasn’t the chapel I was looking for, but it turned out to be much more interesting. The church at Judenstein has a history. The story goes like this: in 1462 (or so) a three-year-old boy named Anderl (diminutive for Andreas) Oxner went missing from his village. His body was found later, in the area. (This much might be true.) Roughly a hundred and fifty years later, a counter-reformationist and anti-Semite named named Hippolyt Guarinoni invented a story about Anderl’s death which he modeled after a popular story going around at the time involving a little boy named Simon in the city of Trent (as in the Council of Trent.) In Guarinoni’s new fable, traveling Jewish merchants bought the boy from his stepfather, then performed a ritual murder, cutting his throat open and collecting the blood. Guarinoni got a lot of traction out of this story, and with it built a church on the scene of the alleged crime and started up a cult venerating the “martyred” child. On top of this the Brothers Grimm picked up the story and took it all over Europe, if not the world, in their tale “Der Judenstein” (The Jews’ Stone).

It wasn’t the chapel I was looking for, but it turned out to be much more interesting. The church at Judenstein has a history. The story goes like this: in 1462 (or so) a three-year-old boy named Anderl (diminutive for Andreas) Oxner went missing from his village. His body was found later, in the area. (This much might be true.) Roughly a hundred and fifty years later, a counter-reformationist and anti-Semite named named Hippolyt Guarinoni invented a story about Anderl’s death which he modeled after a popular story going around at the time involving a little boy named Simon in the city of Trent (as in the Council of Trent.) In Guarinoni’s new fable, traveling Jewish merchants bought the boy from his stepfather, then performed a ritual murder, cutting his throat open and collecting the blood. Guarinoni got a lot of traction out of this story, and with it built a church on the scene of the alleged crime and started up a cult venerating the “martyred” child. On top of this the Brothers Grimm picked up the story and took it all over Europe, if not the world, in their tale “Der Judenstein” (The Jews’ Stone).  The little church, while quite lovely, has frescos on the ceiling depicting the disappearance of Anderl (one shows the grief of his mother when, while working in the fields, she learns of her son’s death). If you visit this church the one fresco you will NOT see is the one which was (thankfully) painted over — depicting little Anderl actually being cut open by Jewish men. I kid you not, I wish I were.

The little church, while quite lovely, has frescos on the ceiling depicting the disappearance of Anderl (one shows the grief of his mother when, while working in the fields, she learns of her son’s death). If you visit this church the one fresco you will NOT see is the one which was (thankfully) painted over — depicting little Anderl actually being cut open by Jewish men. I kid you not, I wish I were.  I need to point out that, while the Roman Catholic church was instrumental in this kind of story gaining traction to begin with, in 1953 Paul Rusch, then Bishop of Innsbruck, struck the holiday commemorating Anderl’s “martyrdom” from the church calendar. In the 1980s Bishop Reinhold Stecher began to dismantle the cult by having Anderl’s bones removed from the altar, ordering the offending fresco to be painted over, and officially banning the cult from the church (in the 1990s). There is now a plaque inside the church explaining the myth and it’s falsehood. Problem was, by that time Anderl’s fans were not to be dissuaded — the annual pilgrimages occur every July on Anderl’s “day”, hosted privately (i.e. not through the Church) by various right wing extreme factions and Catholic fundamentalists. Tirol’s anti-Semitic and anti-other roots are complicated — more religious than racial, reflecting the fear of outsiders often encountered in mountain people, and encouraged by the church (right there alongside hatred toward heretics and Protestants) by calling Jews Christ-killers and all that other fun stuff. Then the Nazis took over and took things to extremes. Today, religion plays little part in the local bigotry. The right-wingers tend to harp on “preserving our way of life and our culture”, and work on keeping brown people and Slavs out. (Note to the BZÖ: It’s not working.) The right-leaning view Turks and other eastern European nationals today much in the same way American wingnuts view Mexican and Central American immigrants to the U.S. At the turn of the last century, even Italians were suspect. I know of a family who won’t talk to one of their daughters because she married a German. And another who can’t accept their daughter-in-law, for the crime of being (gasp) Swiss. I am speaking of things I have heard and personally learned, not of Tiroleans in general — there are lots of friendly and open-minded people here too, especially in the cities but out in the countryside as well. But things like this, the stuff not talked about, are embedded in the culture.

I need to point out that, while the Roman Catholic church was instrumental in this kind of story gaining traction to begin with, in 1953 Paul Rusch, then Bishop of Innsbruck, struck the holiday commemorating Anderl’s “martyrdom” from the church calendar. In the 1980s Bishop Reinhold Stecher began to dismantle the cult by having Anderl’s bones removed from the altar, ordering the offending fresco to be painted over, and officially banning the cult from the church (in the 1990s). There is now a plaque inside the church explaining the myth and it’s falsehood. Problem was, by that time Anderl’s fans were not to be dissuaded — the annual pilgrimages occur every July on Anderl’s “day”, hosted privately (i.e. not through the Church) by various right wing extreme factions and Catholic fundamentalists. Tirol’s anti-Semitic and anti-other roots are complicated — more religious than racial, reflecting the fear of outsiders often encountered in mountain people, and encouraged by the church (right there alongside hatred toward heretics and Protestants) by calling Jews Christ-killers and all that other fun stuff. Then the Nazis took over and took things to extremes. Today, religion plays little part in the local bigotry. The right-wingers tend to harp on “preserving our way of life and our culture”, and work on keeping brown people and Slavs out. (Note to the BZÖ: It’s not working.) The right-leaning view Turks and other eastern European nationals today much in the same way American wingnuts view Mexican and Central American immigrants to the U.S. At the turn of the last century, even Italians were suspect. I know of a family who won’t talk to one of their daughters because she married a German. And another who can’t accept their daughter-in-law, for the crime of being (gasp) Swiss. I am speaking of things I have heard and personally learned, not of Tiroleans in general — there are lots of friendly and open-minded people here too, especially in the cities but out in the countryside as well. But things like this, the stuff not talked about, are embedded in the culture.

UPDATE: (16 February 2011): I have come across a book about pre-Christian finds in Austria, which has this to say about the Judenstein (translated here by me):

The “Judenstein” was without a doubt once an altar, where people had been once ritually sacrificed… According to the legend, after the murder, the Jews hung the boy from a birch tree. “That is a purely Heathen story, nothing Christian nor Jewish in it”, writes Norbert Mantl in his 1967 book about pre-Christian cult relics in the Upper Inn Valley. “The saga deals with the memory of an ages-old fertility sacrifice whose ritual is still recognizable. Blood was spilled over the stone and the birch, representing all plant life necessary to humans, receiving the corpse as an offering. It had to do with fertility and a good harvest, but also for the welfare and prosperity of humans and their animals.”

So it is possible that the story did not get made up out of thin air, but was a contorted version of a much older “enemy” of the church, refitted for the Middle Ages.

>Amsel und Freund, 2

>Nostalgietour: Andreas Hofer

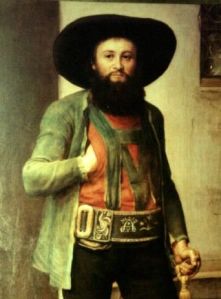

>Every Tirolean schoolchild knows who Andreas Hofer is, if not all the details of his life and circumstances. He is, simply put, Tirol’s best-known and most beloved Freedom Fighter. The man who organized successful resistance to Tirol’s being taken by the Bavarians (France’s ally in the Napoleonic Wars — don’t expect me to explain this long, drawn-out, revolving-cast war period. It’s too complicated for my opera singer’s brain. Suffice to say, they kept coming up with treaties, and Austria kept promising Hofer that Tirol would not be given away. And then it’d be given away.) A man betrayed by one of his own people, court-martialled and executed in Italy (Napoleon was King of Italy as well at the time. I told you it was complicated), and forever after a symbol of fierce Tirolean Independence. He was Ethan Allen and Nathan Hale rolled into one.

The site of Hofer’s most famous adventure, the Battle of Bergisel, is now home to a museum and a park with Monarchy-era monuments and statues, including the one below. The plaque at the base reads Für Gott, Kaiser und Vaterland. The Battle of Bergisel took place in 1809, and it is this year which is most closely identified with Hofer. 2009 being the 200th anniversary, there is much going on as far as cultural events and awareness in Innsbruck.

The site of Hofer’s most famous adventure, the Battle of Bergisel, is now home to a museum and a park with Monarchy-era monuments and statues, including the one below. The plaque at the base reads Für Gott, Kaiser und Vaterland. The Battle of Bergisel took place in 1809, and it is this year which is most closely identified with Hofer. 2009 being the 200th anniversary, there is much going on as far as cultural events and awareness in Innsbruck.

Just above the park is the entrance to the Bergisel Sprungschanze (ski jump), which I will cover at a later date.

Just above the park is the entrance to the Bergisel Sprungschanze (ski jump), which I will cover at a later date.