>The Mittenwaldbahn (a railway to Munich which goes through some splendid mountain scenery, and I do mean through — it’s all bridges and tunnels til Bavaria) stops in the village of Reith bei Seefeld, which claims a cultural walking tour of sorts through it and its neighboring village, Leithen. Some of it was the usual, chapels and Madonnas, but a few items were interesting.

Reith saw its share of suffering from the World Wars — from the two wars it lost 28 men, which doesn’t sound like much until you remember how small this village is. Then in 1945 the Allies bombed it six times, dropping 300 bombs in attempts to destroy the rail line. This is an Allied bombshell from the time. (Note: Tirol was occupied by British forces after the war.)

Reith saw its share of suffering from the World Wars — from the two wars it lost 28 men, which doesn’t sound like much until you remember how small this village is. Then in 1945 the Allies bombed it six times, dropping 300 bombs in attempts to destroy the rail line. This is an Allied bombshell from the time. (Note: Tirol was occupied by British forces after the war.)

In Leithen one finds the alleged birthplace of Thyrsus, a 9th-century giant known for being killed by the more-famous Haymon the Giant, who regretted the act enough to build the collegiate church in Wilten. Historical researchers presume that Haymon was a Bavarian aristocrat with neighbor issues; so far I found no light on who Thyrsus really was. He’s the one on the right in this fresco. The saga relates that when Thyrus was slayed, his blood spilled into the ground and became oil shale, as indeed there are shale deposits in the region around Seefeld and Scharnitz.

In Leithen one finds the alleged birthplace of Thyrsus, a 9th-century giant known for being killed by the more-famous Haymon the Giant, who regretted the act enough to build the collegiate church in Wilten. Historical researchers presume that Haymon was a Bavarian aristocrat with neighbor issues; so far I found no light on who Thyrsus really was. He’s the one on the right in this fresco. The saga relates that when Thyrus was slayed, his blood spilled into the ground and became oil shale, as indeed there are shale deposits in the region around Seefeld and Scharnitz.

The Thirty Years’ War brought the Plague to Tirol. A wealthy Innsbruck merchant fled with his family to Leithen and fell ill there, but pledged to built this pillar, painted with scenes from the crucifixion, which he did in 1637. Often one finds not just a pillar but an entire church built out of gratitude for someone’s survival. Evidently many people made a lot of deals with God in the hopes of surviving the Plague, as Pestkirchen are abundant — in fact, there’s one at the end of my street.

The Thirty Years’ War brought the Plague to Tirol. A wealthy Innsbruck merchant fled with his family to Leithen and fell ill there, but pledged to built this pillar, painted with scenes from the crucifixion, which he did in 1637. Often one finds not just a pillar but an entire church built out of gratitude for someone’s survival. Evidently many people made a lot of deals with God in the hopes of surviving the Plague, as Pestkirchen are abundant — in fact, there’s one at the end of my street.

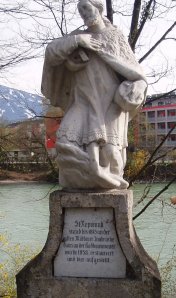

This rock sticking out of the ground would probably have escaped notice completely if not for the list of monuments found on the walking tour, which I picked up at the tourist information desk. It was once a milestone, with the figure of St. Nicholas (Reith’s patron saint) attached to the base. In 1703 Bavarian soldiers (in the War of Spanish Succession) sacked the village and ripped out the saint. Ever since, the base has stood there as a memorial (to what, I’m not sure. Possibly as a reminder to hate the Germans and the French.)

This rock sticking out of the ground would probably have escaped notice completely if not for the list of monuments found on the walking tour, which I picked up at the tourist information desk. It was once a milestone, with the figure of St. Nicholas (Reith’s patron saint) attached to the base. In 1703 Bavarian soldiers (in the War of Spanish Succession) sacked the village and ripped out the saint. Ever since, the base has stood there as a memorial (to what, I’m not sure. Possibly as a reminder to hate the Germans and the French.)

So, the general consensus seems to be that there was a lot of fighting going on, just like anywhere. Centuries of peaceful co-existence, then something happens, blood is shed. And humans memorialize it afterward, as best they can.