>Part of the Schneeferner Glacier on the Zugspitz, Germany’s highest mountain, is getting a big white sunshade put over it for the summer months, to keep it from melting away entirely. The reason for this measure is not purely ecological, but also to help keep the ski slopes up there in business by saving a core section of the ice.

The tarps, 6000 square meters (nearly 65,000 square feet) in total, can be seen in a few photographs at this site (in German.) The Schneeferner has been shrinking considerably in the last 40 years; it is feared that the glacier may disappear by 2030.

Category Archives: Germany

>Four Catholic priests from Tirol and Vorarlberg

>From a booklet* I came across while visiting a village church. I’m not much into organized religion but since organized religion isn’t forcing me to live their way, I don’t hold anything against it.

That said, as all personal (and especially local) stories out of the time of the Third Reich interest me, I am passing these along. Four individuals is not much of a resistance in the time of Cardinal Innitzer, who, despite having said publicly that “There is only one Führer: Jesus Christ”, seemed to bend over backward to make the Nazis feel at home in Vienna. One assumes there were many others who simply kept their heads low, and others who used the political situation to their own benefit. Probably there were many who started out in vocal opposition, but then got a stiff warning (such as a few years at Buchenwald or Dachau) and stayed quiet for the duration of the Reich. These four priests did not quiet down, even under intense pressure to do so. For that, they paid with their lives.

Born, raised and ordained as a priest in Tirol, Neururer was working in the village of Götzens near Innsbruck when Hitler took over Austria. Probably watched carefully due to his activities with the Christian Social Movement, but brought in for “slander to the detriment of German marriage” when he advised a Tirolean woman against marrying a divorced man (who happened to be a Nazi and a friend of the Gauleiter.) Sent to Dachau, then Buchenwald. At Buchenwald in 1940 he baptized a fellow inmate, and was found out. He was hanged upside down from chains until he died, 34 hours later.

From Tirol, ordained in Fribourg, Switzerland. Worked in Graz until the Anschluss, when his superiors sent him home to Tirol, hoping to avoid problems. He continued however, to speak out against Hitler, was banned from teaching, and urged to leave the country. The Gestapo followed him to Spain, and two agents posing as exiled Jews seeking catholic instruction befriended him and managed to get him over the border into Nazi-occupied France, where he was promptly arrested. He was brought to Berlin, and was tried and beheaded in 1943.

Carl Lampert

From Vorarlberg, ordained and active in Tirol. Remained an outspoken protester of National Socialist church policy despite several arrests, and time at Dachau and Sachenhausen concentration camps. Released in 1941 and moved to northern Germany, he was brought in again on charges of treason, spying, disrupting the war effort, consorting with the enemy and listening to foreign radio broadcasts (this last charge alone was punishable by death.) He was sentenced to death and beheaded in 1944.

Franz Reinisch (link in German)

Also from Vorlarberg, Reinisch was able to steer clear of the Nazis during his young career (he spent time studying law and then theology into the 30s), but was banned from speaking publicly by the Gestapo in 1940. He continued work in the church as a translator, in 1941 called up to the Wehrmacht, which includes a mandatory oath of allegiance to Hitler. This he refused to do, knowing it meant certain death. In 1942 he was arrested, tried, convicted and beheaded.

* Bischöfliches Priesterseminar Innsbruck-Feldkirch Heft 101 — Sommersemester 2008

>Speaking About The Past

>Visited a Saturday morning flea market in the Altstadt last weekend, picked up some used books, including one out-of-print book titled “Man muß darüber reden” (“One Must Speak About It”), a collection of talks given by Nazi concentration camp survivors to classes of schoolchildren (high school age, one assumes, since the stories are pretty detailed) in the 1970s-80s. The book is really an interesting read, not only for the survivors’ stories, but for the questions asked by the pupils — sometimes naive, sometimes incredibly direct, and often questions that an adult would not be able to bring him- or herself to ask out loud.

For me, there was something new in the stories of how they came home after the war — and I find this is a big hole in my knowledge of the holocaust. How did people get home, did they have any help. how were they treated by their neighbors, was anything said about the past? And, the biggest question for me, why did they return to their homes, and not emigrate to other coutries, like many others? Some of the speakers in the book were Jewish, some had been Communists or otherwise politically active somehow against the Nazis, some were simply unlucky. They all, each and every one, spoke of how it was luck that enabled them to survive — luck and solidarity among the inmates, although solidarity alone didn’t help millions of others.

According to some accompanying words from a government minister at the back of the book, these talks are now a regular part of the school experience in Austria. I don’t know if that’s still true, given that the ages of survivors must be fairly advanced now. I need to ask some of my home-grown friends about it.

One often hears that Austrians have not come to terms with its Nazi past, and that may be true but it’s not for lack of effort by liberal-thinking people. There have been steps, small steps, all along the way. They are not always easy to see, especially by us Ausländer who see the xenophobic side of society often enough. But it’s most definitely part of The Discussion, and that offers hope.

>Spuren der DDR: Denkmale

>Freiberg is a pleasant small town in the state of Sachsen (Saxony), not far from Dresden. It has an old medieval wall and a pretty Altstadt, and a renowned Mining Academy. The locally made Nutcrackers, Christmas pyramids and other wooden figures are popular all over the world.

And, being within the former Deutsche Demokratische Republik, it has scars from both the Second World War and the Cold War, although they’re not immediately obvious. During a walk around the outskirts of town on Christmas Day , we stumbled upon a few of them.

The monument above is in the center of the Russian Cemetery, the resting place of Soviet soldiers who fell in battle.

The monument above is in the center of the Russian Cemetery, the resting place of Soviet soldiers who fell in battle.

Not far from it we found a smaller monument in memory of concentration camp victims. The letters KZ in a triangle at the top is the short form for Konzentrationslager. The text reads, Euch unsterbliche Opfer des Faschismus nie zu vergessen sei unsere Pflicht (It is our duty never to forget you, the immortal victims of fascism.)

Not far from it we found a smaller monument in memory of concentration camp victims. The letters KZ in a triangle at the top is the short form for Konzentrationslager. The text reads, Euch unsterbliche Opfer des Faschismus nie zu vergessen sei unsere Pflicht (It is our duty never to forget you, the immortal victims of fascism.)

We Americans tend to think of German concentration camps being exclusively for Jews, and of course they were the special targets of the Nazis. However, and especially in the early years of the Third Reich, just about anyone who didn’t fit into Hitler’s plans — communists, homosexuals, protesting clergy, pacifists, gypsies, criminals, outsiders — was threatened with incarceration and eventual execution. East Germany’s post-war government put special emphasis on the oppression of communists, obviously to keep their Soviet overlords happy, and also to help along the myth that there were no Nazis in the GDR.

One block further down the hill we came to another kind of memorial — for the ethnic Germans, forced out of their homes in the east after the war, who died in the refugee camps at Freiberg. This was the final stop for 1,375 men, women and children from East Prussia, Pomerania, Silesia and Sudetenland, and they died of the usual refugee-related causes: injuries, hunger, cold, exhaustion.

One block further down the hill we came to another kind of memorial — for the ethnic Germans, forced out of their homes in the east after the war, who died in the refugee camps at Freiberg. This was the final stop for 1,375 men, women and children from East Prussia, Pomerania, Silesia and Sudetenland, and they died of the usual refugee-related causes: injuries, hunger, cold, exhaustion.

Again, I realize that the near-automatic response to this is often “They had it coming.” It is important to remember, however, that these Germans had been settled in those far-off regions for hundreds of years, and many of them had no more political connection to the Fatherland than did the Pennsylvania Dutch . They ended up being just another group of people to suffer from Hitler’s follies, if indirectly, but just as fatally.

I’ve been reading Anna Segher’s “Transit”, a novel set in Marseilles in 1940 and populated with all sorts of people fleeing the Nazi regime. Pushed to the coasts in front of the advancing German troops, they stand in all sorts of consular lines waiting for their visas — entry visas, exit visas, transit visas necessary for passing through one or more countries on route to another, places on board departing ships. One would wait for that last piece of paper with the official stamp from the proper authorities, only to get it after another had passed its expiration date.

Much of the book must have been taken from her own experiences and those of countless friends, as she fled Germany herself in 1933, first to France and then to Mexico. Much of what happened in her best-selling novel “The Seventh Cross” (later made into a film starring Spencer Tracey) came from information from camp escapees, as well pure speculation as to what was going on inside the Reich. Although she clearly didn’t know about the extent of the Holocaust while she was writing, she conveys quite well the minute-to-minute anxiety of being on the run in a paranoid, fearful country.

A dedicated enthusiast to the cause of a “better Germany”, Seghers moved to the East after the war and, like Brecht, was held up as an example of the literature of communist East Germany. “The Seventh Cross” was required reading in the schools. Naturally, I had never even heard of her.

>Münchner Synagoge

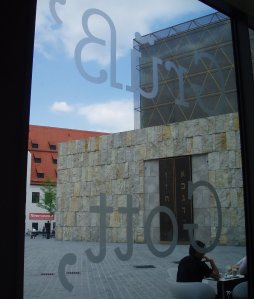

> We were in the area of the new (2006) Munich Synagogue recently, on Jakobsplatz. There are three separate buildings, actually — the temple (the massive block seen below), the Jewish Museum (opened in 2007) and the Community Center. We did not go into the museum, having just emerged from one (I can only soak in so much cultural information in one afternoon) but we noted that its glass walls are covered in written conversations between Jews and non-Jews and their feelings toward each other, and about what happened right here in Munich. Most of it is in English, and it’s very interesting to read.

We were in the area of the new (2006) Munich Synagogue recently, on Jakobsplatz. There are three separate buildings, actually — the temple (the massive block seen below), the Jewish Museum (opened in 2007) and the Community Center. We did not go into the museum, having just emerged from one (I can only soak in so much cultural information in one afternoon) but we noted that its glass walls are covered in written conversations between Jews and non-Jews and their feelings toward each other, and about what happened right here in Munich. Most of it is in English, and it’s very interesting to read.

Lunch nearby; sometimes one finds English in unexpected places.

Lunch nearby; sometimes one finds English in unexpected places.

>Bernried

> Last week we took a little excursion through the Bavarian lake region. First stop was lunch, in the Biergarten of a very nice cloister, where the specialty is Schweinhaxe (pork knuckle) and Knödel. We had a great view of the countryside.

Last week we took a little excursion through the Bavarian lake region. First stop was lunch, in the Biergarten of a very nice cloister, where the specialty is Schweinhaxe (pork knuckle) and Knödel. We had a great view of the countryside.

Next stop was Bernried, a village on Lake Starnberg and home to the museum housing the art collection of Lothar-Günter Buchheim, whom Americans may recognize as the author of “Das Boot.” Apparently he was a colorful figure, and quite the collector of German expressionist paintings, primitive folk art, and carousel horses, among other things.

This artwork was parked in front of the museum. The seaweed draped over it is made from bicycle chains. The creature on the roof has already got his tentacles into some of the windows.The artist is local.

>Militärgebäude

>Occasionally people will say that some neglected eyesore of a building looks like something “aus der DDR”, when it has that look of faded, socialist-architecture glory about it. My boyfriend says this too, and he should know, having grown up there.

In Munich there is a particular building, attached to a complex of similar buildings, which has this look; massive, with small windows (for more fortress-like protection in case of attack), peeling paint, grass growing in the parking lot. Former Soviet Embassy? Gestapo building? Nope.

In Munich there is a particular building, attached to a complex of similar buildings, which has this look; massive, with small windows (for more fortress-like protection in case of attack), peeling paint, grass growing in the parking lot. Former Soviet Embassy? Gestapo building? Nope.

It’s OURS. Or was. This branch of the University of Maryland served mainly the children of soldiers stationed here at the neighboring McGraw base (now closed) and other bases in southern Germany. In 1992 the university moved its facilities to Augsburg, and then to Mannheim, where it is set to close any day (in May, I think.) A cursory internet search tell me that the Munich police now use the building, but for some reason they’ve left those letters hanging up there (and falling down) and haven’t bothered to repaint. I am not quite sure who actually owns these buildings now, and that might be the problem.

Like the war bunkers and monuments, these military-related buildings are reminders of a time past, when the cold war was in full swing.