> Weird local news of the week: This article turned up in the headlines at the U.S. version of Google News. Assuming that there must be a local discussion going on, I searched the German-language google sites as well as the local papers but found very little. Funny how it ended up over on the U.S. site, then. Do you think there are people who trawl the nets looking for anything that might remotely resemble a sex scandal?

Weird local news of the week: This article turned up in the headlines at the U.S. version of Google News. Assuming that there must be a local discussion going on, I searched the German-language google sites as well as the local papers but found very little. Funny how it ended up over on the U.S. site, then. Do you think there are people who trawl the nets looking for anything that might remotely resemble a sex scandal?

INNSBRUCK, Austria (AP) – An anti-pornography activist wants officials in the Alpine city of Innsbruck to take down a large crucifix bearing a sculpture of a naked Jesus Christ.

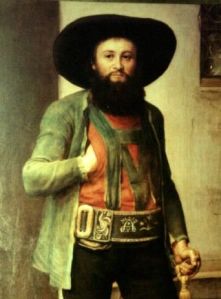

Martin Humer, who gained notoriety last year after he painted part of a statue of a nude Mozart and stuck feathers on it, is pressuring authorities to remove the crucifix from a public square where it has been displayed for 20 years, public broadcaster ORF reported Thursday.

Humer, an 82-year-old former photographer, said he and about 100 supporters were organizing a protest for Friday.

Mayor Hilde Zach dismissed the fuss and said she would refuse to remove the crucifix, insisting it is a work of art and is in no way pornographic.

Here’s a photo of the crucifix so you can see it for yourself. Not only is this Jesus naked, he’s appears to be completely sexless as well.

I like Frau Zach. She’s not only a big supporter of the arts, she actually comes to concerts and theater performances on a regular basis. Local musician friends have told me that several of them were waiting outside a classical concert venue, ticketless, when the Mayor arrived. Learning that they had no tickets and that the concert was sold out, she went in and arranged standing room for them. She’s OK in my book.