>Neither had I. She has been awarded the 2009 Nobel Prize for Literature.

More significantly, neither had the beau, who is knows a lot about European literature. Wikipedia, in its entry on Müller, says that prior to the award, Müller was little-known outside Germany and even there was known only among a minority of intellectuals and literary critics.

Her writings look like they would fit right in with the other books on my shelves, many of which deal with people trying to remain alive and human under communism, nazism, or any other repressive regime. I plan to pick up a copy of Atemschaukel (the English title, when it comes out, will be Everything I Possess I Carry With Me) pretty soon.

It’s also a welcome story within a larger topic which gets a lot of criticism just for being a topic — the post-war deportation of ethnic Germans from eastern European lands, force-marched either westward into Germany (those that made it alive were the lucky ones) or to Soviet gulags, as was the case with Müller’s own mother.

I am reminded of Gregor Himmelfarb, whose book about his post-war experiences shares similarities with Müller’s latest protagonist, Leo Auberg. Himmelfarb was born in the state of Mecklenburg, Germany, and grew up in the ethnic-German region Siebenbürgen, in Romania. When Germans in Romania were required to obtain Aryan identity cards, Himmelfarb learned for the first time that his Russian father was Jewish. Managing to survive the war, he then faced new difficulties for being the son of a factory-owning “exploitative capitalist”, and above all for being “German”. The Israeli immigration services weren’t much help, as they considered him “not Jewish” (he was finally able to emigrate in 1952.)

Every group of people is made up of individuals, all with their own stories. And, as Herta Müller shows, there are so many unheard stories out there worth learning.

Category Archives: memory

>Militärfriedhof

> I admit it, I find some cemeteries interesting. On a recent outing we passed by the Pradl Cemetery, the southeast corner of which holds a military section. Above is a monument erected by Italy in memory of the Italian soldiers who died in Tirolean military hospitals. Below, their graves.

I admit it, I find some cemeteries interesting. On a recent outing we passed by the Pradl Cemetery, the southeast corner of which holds a military section. Above is a monument erected by Italy in memory of the Italian soldiers who died in Tirolean military hospitals. Below, their graves.

A monument erected by the Soviets to honor their fallen victims of the “German Fascists” (Nazis).

A monument erected by the Soviets to honor their fallen victims of the “German Fascists” (Nazis).

The markers below were not immediately recognizable to us from a distance, but their import became clearer when we recognized that each is capped with a red fez. They are the graves of Bosnian Muslims who’d fought for the Austrian Empire in World War I. Their graves face east.

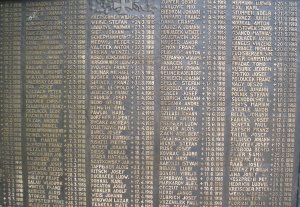

One of several plaques of names of the fallen. Names upon names upon names. Nearby are graves of POWs, victims of the nearby concentration camp (in Reichenau), forced laborers from Poland. It looks to me as if it was first planned that each group have its own separate area, but that as the dead began to add up, they were put here wherever there was room for them — leading to an interesting mish-mash in some corners of soldiers and civilians, equal and side by side in death.

One of several plaques of names of the fallen. Names upon names upon names. Nearby are graves of POWs, victims of the nearby concentration camp (in Reichenau), forced laborers from Poland. It looks to me as if it was first planned that each group have its own separate area, but that as the dead began to add up, they were put here wherever there was room for them — leading to an interesting mish-mash in some corners of soldiers and civilians, equal and side by side in death.

This part of the cemetery, while maintained and spotless, looks as if very few people come here. And why should they — these graves are very old, and their occupants are from far away lands.

>Reith bei Seefeld

>The Mittenwaldbahn (a railway to Munich which goes through some splendid mountain scenery, and I do mean through — it’s all bridges and tunnels til Bavaria) stops in the village of Reith bei Seefeld, which claims a cultural walking tour of sorts through it and its neighboring village, Leithen. Some of it was the usual, chapels and Madonnas, but a few items were interesting.

Reith saw its share of suffering from the World Wars — from the two wars it lost 28 men, which doesn’t sound like much until you remember how small this village is. Then in 1945 the Allies bombed it six times, dropping 300 bombs in attempts to destroy the rail line. This is an Allied bombshell from the time. (Note: Tirol was occupied by British forces after the war.)

Reith saw its share of suffering from the World Wars — from the two wars it lost 28 men, which doesn’t sound like much until you remember how small this village is. Then in 1945 the Allies bombed it six times, dropping 300 bombs in attempts to destroy the rail line. This is an Allied bombshell from the time. (Note: Tirol was occupied by British forces after the war.)

In Leithen one finds the alleged birthplace of Thyrsus, a 9th-century giant known for being killed by the more-famous Haymon the Giant, who regretted the act enough to build the collegiate church in Wilten. Historical researchers presume that Haymon was a Bavarian aristocrat with neighbor issues; so far I found no light on who Thyrsus really was. He’s the one on the right in this fresco. The saga relates that when Thyrus was slayed, his blood spilled into the ground and became oil shale, as indeed there are shale deposits in the region around Seefeld and Scharnitz.

In Leithen one finds the alleged birthplace of Thyrsus, a 9th-century giant known for being killed by the more-famous Haymon the Giant, who regretted the act enough to build the collegiate church in Wilten. Historical researchers presume that Haymon was a Bavarian aristocrat with neighbor issues; so far I found no light on who Thyrsus really was. He’s the one on the right in this fresco. The saga relates that when Thyrus was slayed, his blood spilled into the ground and became oil shale, as indeed there are shale deposits in the region around Seefeld and Scharnitz.

The Thirty Years’ War brought the Plague to Tirol. A wealthy Innsbruck merchant fled with his family to Leithen and fell ill there, but pledged to built this pillar, painted with scenes from the crucifixion, which he did in 1637. Often one finds not just a pillar but an entire church built out of gratitude for someone’s survival. Evidently many people made a lot of deals with God in the hopes of surviving the Plague, as Pestkirchen are abundant — in fact, there’s one at the end of my street.

The Thirty Years’ War brought the Plague to Tirol. A wealthy Innsbruck merchant fled with his family to Leithen and fell ill there, but pledged to built this pillar, painted with scenes from the crucifixion, which he did in 1637. Often one finds not just a pillar but an entire church built out of gratitude for someone’s survival. Evidently many people made a lot of deals with God in the hopes of surviving the Plague, as Pestkirchen are abundant — in fact, there’s one at the end of my street.

This rock sticking out of the ground would probably have escaped notice completely if not for the list of monuments found on the walking tour, which I picked up at the tourist information desk. It was once a milestone, with the figure of St. Nicholas (Reith’s patron saint) attached to the base. In 1703 Bavarian soldiers (in the War of Spanish Succession) sacked the village and ripped out the saint. Ever since, the base has stood there as a memorial (to what, I’m not sure. Possibly as a reminder to hate the Germans and the French.)

This rock sticking out of the ground would probably have escaped notice completely if not for the list of monuments found on the walking tour, which I picked up at the tourist information desk. It was once a milestone, with the figure of St. Nicholas (Reith’s patron saint) attached to the base. In 1703 Bavarian soldiers (in the War of Spanish Succession) sacked the village and ripped out the saint. Ever since, the base has stood there as a memorial (to what, I’m not sure. Possibly as a reminder to hate the Germans and the French.)

So, the general consensus seems to be that there was a lot of fighting going on, just like anywhere. Centuries of peaceful co-existence, then something happens, blood is shed. And humans memorialize it afterward, as best they can.

>Speaking About The Past

>Visited a Saturday morning flea market in the Altstadt last weekend, picked up some used books, including one out-of-print book titled “Man muß darüber reden” (“One Must Speak About It”), a collection of talks given by Nazi concentration camp survivors to classes of schoolchildren (high school age, one assumes, since the stories are pretty detailed) in the 1970s-80s. The book is really an interesting read, not only for the survivors’ stories, but for the questions asked by the pupils — sometimes naive, sometimes incredibly direct, and often questions that an adult would not be able to bring him- or herself to ask out loud.

For me, there was something new in the stories of how they came home after the war — and I find this is a big hole in my knowledge of the holocaust. How did people get home, did they have any help. how were they treated by their neighbors, was anything said about the past? And, the biggest question for me, why did they return to their homes, and not emigrate to other coutries, like many others? Some of the speakers in the book were Jewish, some had been Communists or otherwise politically active somehow against the Nazis, some were simply unlucky. They all, each and every one, spoke of how it was luck that enabled them to survive — luck and solidarity among the inmates, although solidarity alone didn’t help millions of others.

According to some accompanying words from a government minister at the back of the book, these talks are now a regular part of the school experience in Austria. I don’t know if that’s still true, given that the ages of survivors must be fairly advanced now. I need to ask some of my home-grown friends about it.

One often hears that Austrians have not come to terms with its Nazi past, and that may be true but it’s not for lack of effort by liberal-thinking people. There have been steps, small steps, all along the way. They are not always easy to see, especially by us Ausländer who see the xenophobic side of society often enough. But it’s most definitely part of The Discussion, and that offers hope.